Chapter 7 A Model for a Philosophical View of IoT

“The trick to forgetting the big picture is to look at everything close up.”

— Palahniuk (2003, chap. 3, para. 73)

7.1 Introduction

Having built a foundation for this research in its different areas of concern (IoT, Philosophy, Design) and established the applicability of RtD and playful speculation through carpentry as core methodologies, we can now begin crafting our artefacts. In total this research presents three artefacts each exploring a carpentered approach at viewing IoT through a lens of philosophy, each imagining alternative approaches towards the design of IoT systems. Metaphor plays a key role in understanding these artefacts, and after the previous chapters there should be an established familiarity with its presence in this thesis. I wish there was a better way to represent but since metaphors are a common occurrence in philosophy as an explanatory asset (Pepper 1982; Johnson 1995) it was difficult to divorce this work from its use.

In Chapter 3, I gave an introduction to why IoT was important, its place in this discourse with philosophy, and the potential use of constellations (J. G. Lindley and Coulton 2017) as a metaphor for viewing how IoT systems function. In order to use this lens in practicing design this first artefact attempts to grasp the concept of what a philosophical approach at designing for IoT could be like, by presenting a potential framework around which such discourse may take place. This framework intends to guide the carpentry of further artefacts that may be understood in this manner, devised through a model of how IoT objects interact and where those interactions may happen. The act of creating this framework may itself be considered an attempt at carpentry for creating a means to understand the alien phenomenologies existing among digital interactions within IoT. As such, the model at the end of this chapter may aspire to be a secondary major contribution of this research allowing a potential representation of seeing IoT through a philosophical lens. It also is our first step towards addressing the first sub-question of this thesis:

- Is it possible to highlight potential problematic effects emanating off IoT products and services approaches through an object-oriented lens?

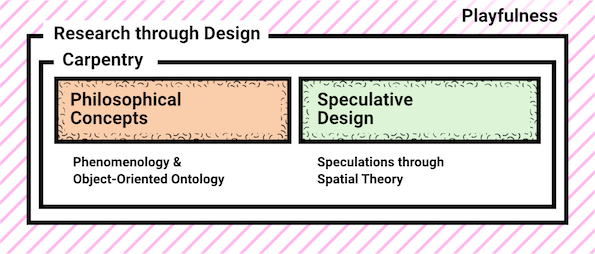

In order to address this question a base understanding of interactions occurring within IoT and between objects on and not on the Internet must be established. For the purposes of taking a non-anthropocentric perspective, this needs to be approached through relevant philosophical discourse or object-oriented-ness, and as explained in the previous chapter, this weaving of philosophical discourse within technology and design is done through an assemblage of methods (Fig. 7.1).

Figure 7.1: The method assemblage for the carpentry of this artefact explores playful appropriations of object-oriented philosophies and the use of speculation through an understanding of spatial theories.

Therefore, in this chapter I will be making a comparison between concepts from philosophy and spatial theories coming from geography and architecture. The reason for this is because IoT interactions occur in both physical and non-physical locations such as a living room and a digital wallet. This comparison is then applied using a philosophical perspective of phenomenological configurations and how they are understood through digital technologies and digital spaces, coming from a review of relevant literature and case studies. This presents an opportunity for exploring IoT’s ontology from human and non-human-centred perspectives in the different manners of interactions capable within it. As such, ludic design discussed in the previous chapter will not be explored in this artefact as this is more to establish a core understanding through playful appropriations of philosophy for further curious explorations in the subsequent chapters. Towards the end this artefacts contribution towards manifesting playfulness within the design process is also touched upon in light of the evidence presented in this chapter.

The first portion of this chapter defines the logic behind how the framework is established followed by a detailed definition of the different elements that create the final model. The model itself becomes the presented artefact in this chapter. To begin I will define philosophical arguments used throughout building a case for seeing IoT interactions as phenomenon existing within multiple spatial configurations.

7.2 IoT as a spatial phenomenon

An earlier definition of IoT I gave was of an amalgamation of heterogeneous physical objects connected through the Internet. The Internet itself, I explored as a ‘space’ where unique non-physical interactions occurred. Colloquially when we refer to the Internet it takes the form of a place that was or will be visited. In this regard, we have seen both the Internet and IoT through phenomenology. To define a structure for our philosophical lens of IoT to sit upon, we need to go back to basics. For that I will be doing two things, (a) presenting a means for dividing digital/non-digital spaces in light of philosophical texts, and (b) mapping the rules that may define interactions that occur within these spaces.

The discussion here is an expansion of the discourse presented in Chapter 4. What we know is that phenomenological research attempts to understand the experience of things and events through the “perspectives and views of physical or social realities” (Leedy and Ormrod 2016, 84). It is in all respects a “first-personal mode of presentation” for any given phenomenon, defining unique meanings of things present in our experience (Smith 2016, 140). As Cole (2013, 160) describes, OOO explores how objects “should be recognised for their indifference to us”, focusing on the things they do “behind our backs” (2013, 160). This view sees the individual experiences of objects as actants moving in and out of their own made assemblages.

So, how does phenomenology fit into this development of a framework? The idea of crafting models of realities is not alien to philosophy. When understanding phenomenon, a core axiom is presenting the relation between our senses and the experience with reality.

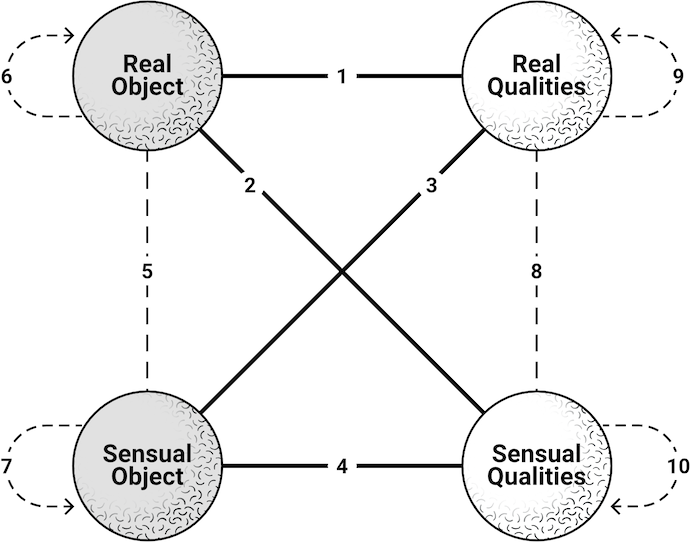

Figure 7.2: Harman (2011b) presented the four-fold quadruple object model for understanding phenomenological perception and relations. Each line represents a possible means for causation defining a specific ontographical relationship.

While explaining the philosophical grounding of this research, I ended Chapter 4 on OOO giving an introduction into my core philosophical approach. Expanding on that further in The Quadruple Object, Harman (2011b) presents OOO coupling Heidegger’s tool-analysis with Husserl’s phenomenological work presenting a framework for defining phenomenological experience. Harman’s four-fold model (Fig. 7.2) sees the presence of two kinds of objects having two kinds of qualities: Real and Sensual; or Real-Objects (RO) with Real-Qualities (RQ), and Sensual-Objects (SO) with Sensual-Qualities (SQ) 31. This premise argues that objects may not exist without their defining qualities, and it is the interaction with our senses that creates the different modalities a phenomenon may have. This is very much Harman building upon the older model of experience which only viewed primary and secondary qualities for objects (Harman 2011a; Smith 2016).

Harman defines RO as those objects that withdraw from experience having RQ which subsequently may only be understood via scrutiny. In the same note, SO are those that rely on experience to exist with SQ, being similarly experiential. This creates several possible combinations between pairing the different objects and qualities. The history of phenomenological research argues for the presence of rifts or tensions between the different combinations of phenomenon and Harman’s model is no different (Harman 2018, 2011b; Bogost 2012). It is the presence of this tension between the real and sensual that crafts OOO. Harman (2018, 150) defines this rift as “vicarious causation”, taking hints from the medieval Islamic and European philosophical concept of Occasionalism 32.

As an example of a rift in causation, he presents an old occasionalist argument for cotton and fire: “Fire does not burn cotton—it is merely the occasion for God to burn the cotton” (Harman 2010a, 5). What Harman is appropriating here is fire and cotton as real and sensual objects with real and sensual qualities. While intermingling fire does not contact all properties of cotton: smell, softness, etc. They are irrelevant to the flame instead cotton only encounters heat. This should not matter with cotton being non-human, but through the OOO lens there is no prejudice between humans and non-humans. Therefore, the simple fact Harman presents is that objects cannot exhaust the reality of other objects when their natures collide. The interaction between fire and cotton is happening on a level we are unable to view unless we see out from within, in other words through an object-oriented perspective. Harman’s view is this interaction happens on the interiors of the objects. In effect he asks, what are cotton and fire personally experiencing?

I should mention here that Harman’s accounts do not argue for occasionalism, rather they argue for OOO as a perspective in viewing causation. OOO cannot agree to an occasionalist world view (Harman 2018, 150). The overarching argument and connection I am presenting here certainly are for causation of a kind, vis-à-vis interactions in IoT. What should be taken from this is the use of OOO to create foundations for a framework that allows for things to be laid bare for scrutiny and possibly define them through spatial references of their insides and outsides. Before making the connection between the end model and viewing IoT in this manner, we must tackle the second part of this equation and understand what I mean by these spatial configurations.

7.2.1 The division of space

There have been moments when I’ve entered a room and thought, “This is a big space!”, or perhaps gestured to a friend in a movie theatre to say, “There’s a space over here”. Like many I’ve also encountered the idea of ‘personal space’ through proximity, such as in a crowded train. These are colloquial uses of the word space and although the concept involves intuitive use in our daily lives, a definition of space has seen philosophical contention for years (Tuan 1977; Cresswell 2008; Wollan 2003; Casey 2001). However, one thing that all sources do agree upon is that space is different from what a place may be.

Yi-Fu Tuan is often quoted as a key figure and influence in the study of human geography and in defining an argument for space and place. Space is described by Tuan (1977, 34) as “an abstract term for a complex set of ideas”, which he says comes from how “people of different cultures differ in how they divide up their world, assign values to its parts, and measure them” (1977, 34). His definition assumes space in relation to an experience one has with their body and those of others that are intimate in nature, allowing one to arrange space in a manner that it “conforms with and caters to [ones] specific biological needs and social relations” (1977, 34).

Architecturally space is seen through an idea of dimensionality, where it can be measured, yet Tuan is eager to point out that “spatial dimensions such as vertical and horizontal, mass and volume are experiences [also] known intimately to the body” (Tuan 1977, 108). This allows Architecture to traverse the boundary between space and place and interweave spatial theory with phenomenology.

7.2.1.1 Insides and Outsides

Both terms Tuan (1977) argues denote common experiences but they expand on each other’s definitions. “Place is security, space is freedom: we are attached to the one and long for the other” (1977, 3). A home thus becomes a place, differentiating it from being just any space because of the meaning associated with it. Tuan’s exploration of spatial theory is more towards the study and experience of Geography as done by the human actant. But, this idea of a kind-of spatial theory can be appropriated to encompass non-physical locations as well:

“Consider the sense of an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’, of intimacy and exposure, of private life and public space. People everywhere recognise these distinctions, but the awareness may be quite vague.” (Tuan 1977, 107)

The insides and outsides which Tuan refers to are in relation to private and public aspects of spaces and ones interaction with them. The level of interaction a person might have within an open town square compared to their own house would be very different, as different amounts of trust would be associated with these ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ spaces. This space/place relationship transcends into digital environments equally with the “conceiving of cyberspace as a social space” (Slane 2007, 86).

Social media may be seen as a prime example of present inside and outside interactions in digital spaces. On social networks audiences are imagined and interacted with in varying degrees to the extent where audiences are flattened into one singular unit in a phenomenon of “context collapse” (Marwick and Boyd 2011, 122). This means it becomes harder to juggle between the different manners of interactions we would want to facilitate within these digital spaces. For example, interacting with family and friends. The reference of private and public by Tuan (1977) becomes very apparent in these spaces because of an inherent need for security. A physical diary and a web-log may thus be considered ‘insides’ in a manner rather than outsides. In this same light when considering OOO and the above four-fold model the inner workings of objects may equally constitute to existing within an inside-space of the object, even a digital space inside a digital object.

I should make clear that when I say ‘digital space’ I refer to a non-physical location represented by signals of data (digital) and accessible only through mediums such as a computer or similar device. The Internet may be a digital space more easily understandable, as it can only be interacted with through a capable digital interface. The reason I say this is because many IoT interactions don’t necessarily occur over the Internet and may happen on the device themselves. Furthermore, the categorisation of cyberspace by Slane (2007) restricts it to a network of devices which for the purposes of this framework I must expand upon and also include an individual object-oriented perspective.

Having said that, Slane (2007, 85) is of the opinion that cyberspace (or digital space) can be seen as being constructed through social contact and its meaning derived from “the uses to which it is put”. This subsequently also means that digital spaces are capable of “multiple simultaneous incarnations” (2007, 85) and with each incarnation a subsequent private/public aspect may be further imagined. Therefore from the above context, social may be taken liberally to include not only person to person interaction but also thing to thing interaction where digital terminals and objects would be included.

Our IoT devices operate in ‘the cloud’—a common way of expressing the operations of Internet-connected devices. The phrase embodies a physicality for an abstract construct such as the Internet. Verbs such as ‘browsing’, ‘surfing’, ‘streaming’, and ‘going online’ are used to express interacting with Internet-related material; websites, applications, devices, etc. Yet in truth, the Internet and IoT are a series of abstract algorithms operating on computers that execute an illusion of interaction. When you surf you feel the water and acknowledge the physics of the world the water, surfboard, and yourself exist in. The Internet posits the notion of entering a physical space much like entering the world of a book or surfing. Both the Internet and IoT are experiential but not necessarily similar to physical experience.

The social aspect referred to above may thus be viewed from an object-oriented stance and imagined as being between digital and non-digital objects. Furthermore, by exercising insides/outsides of these objects within this object-social context, we enter a means of arguing for the private/public33 aspects of these objects. Things that are not visible/tangible/approachable against those that are. If taking a further aggressive stance towards the object-perspective, this may be seen as a context-collapse of the social interaction of objects within the spaces they occupy.

7.2.1.2 A digital configuration of space

This is an argument in perception stemming from years of empirical studies and observations by philosophers around space, time, and the precedence of objects residing within; some of which I’ve explored in previous chapters. The simplest view is one of Natural Realism described by Maund (2003, 1) through perception as a method of acquiring knowledge of an “objective world” consisting of physical objects and occurrences with them. For instance, a red apple can be perceived sweet only if that knowledge exists a priori for the perceiver along with related knowledge such as it being an apple, red, etc.

The physical objects or ‘things’ in IoT are perceived as objects of the physical world, and for the most part our interactions are predicated by our prior knowledge of interacting with them. Therefore, we anticipate an interaction from an IoT-enabled lightbulb to be similar to a non-IoT one. As seen with the constellation metaphor this is not necessarily always the case as the pressing of a physical button might lead to a chain of interactions happening beneath our level of perception. No amount of physical intervention may then alter that reality. As an example, take a Phillips Hue Bulb an IoT device whose colour of light can be changed by its app or a physical dial. It does not matter which is used for in truth the change happens through digital interactions. As non-digital human objects we interact with both the digital spaces of these IoT devices as well as the physical spaces in which they exist, making our interactions multidimensional happening inside and outside.

By seeing these interactions in digital/non-digital34 spaces existing as a phenomenon, we may attempt to make sense of their complexity using philosophical references in tandem with real-life examples. The question phenomenology begs us to ask is, “What is it like to do or experience [something]?” (Muratovski 2015, 79) opening a platform for empathising with these objects and see from their perspective what these inter-spatial interactions are like (to us, and them).

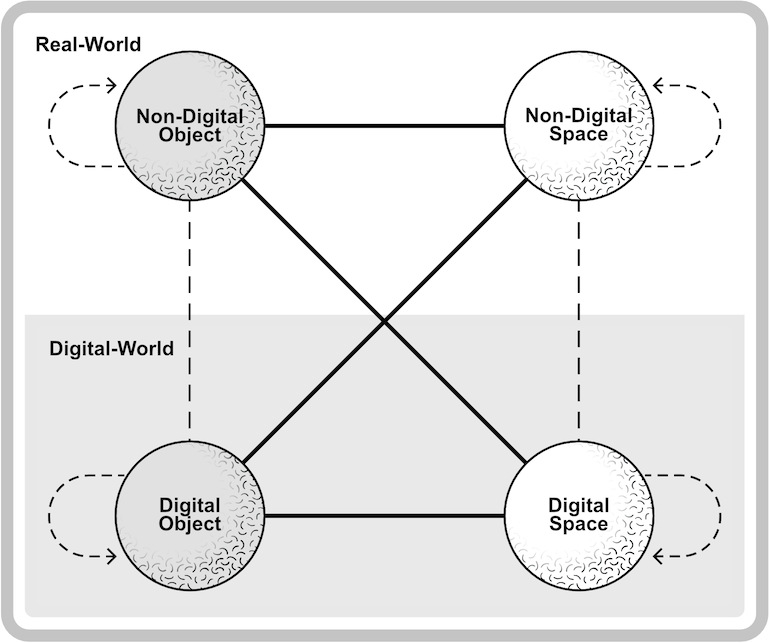

Returning to Harman’s four-fold model we can now juxtapose it with the formulated division of digital and non-digital space (Fig. 7.3). As there may be no precedence between human interaction and non-human interaction through OOO, the four-fold model may be extrapolated for digital objects. Rather than consider their internal qualities which equate to phenomenological experience, what we are concerned with here is their spatial location to define where these interactions occur and their specific ontologies. Where Harman’s model acted upon individual ‘objects’ and experience, this version tackles objects and their locations but specific to an understanding of the digital/non-digital.

Figure 7.3: The appropriated four-fold model for digital/non-digital spaces suggests causality on the insides and outsides of digital/non-digital objects with the possibility of them occurring in tandem in both Real and Digital-Worlds.

The actual space occupied by all our elements is now divided through concepts coming from the above defined perspective of spaces by Tuan (1977), of containing a sense of an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’ presenting two realities. One becomes the non-digital reality that we have around us in which we interact (Real-World or RW), the other being a digital one where interactions through/with digital objects occur (Digital-World or DW). Within them exist both kinds of objects and spaces which exhibit a number of possible interactions. I remind you that the four-fold model is for understanding phenomenological experiences while this utilisation deals with a spatial categorisation of experiences. This juxtaposition captures a possibility of digital interactions existing within non-digital spaces, for instance when you receive a notification on your phone while on the street, or when an IoT lightbulb is switched on in the bedroom using a phone from another room. This model represents a way of categorising these broader experiences through both phenomenology and spatial theory.

The idea of digital being present alongside the non-digital has been discussed by some seeing it as a “virtuality continuum” (Milgram et al. 1995, 285), whereas others consider a space in which “both the real and the virtual [digital] coexist” (Coulton 2017, para. 1). Digital worlds are also seen as literal places that, besides being interpreted as heterogenous global networks, may also be viewed in terms of “space, landscape, and localities” (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 1).

Monk (1997) presents Descartes’ mind/body split as a way to view the physical world through psychological realities such as the digital. These realities have no spatial configurations akin to physical spaces as their locations are “metaphorically ‘in the mind’” (1997, 46). Concepts such as augmented reality or virtual reality might be easier to understand in this context. This logic may be similarly utilised to fathom the realities of digital experiences such as IoT that interweave between the physical and the digital. Therefore, the division of space can be justified through a philosophical embodiment of the virtual space as a similar yet altered parallel space to the physical residing within it.

7.2.2 Reconfiguring Insides and Outsides as Heterotopia

The above model now facilitates a phenomenon of IoT occurring through a kind-of spatial theory, it has a structure but lacks specific context. A more detailed characterisation of the inside/outside would help in grounding this framework better. At the moment this model explores individual interactions between unit entities (digital/non-digital to object/space). In most IoT interactions there occur moments where multiple modalities may exist, such as a digital object in a non-digital space interacting through digital space. Specifying how these spaces interact may solve this and propose further possible combinations. To do that though, I will need to return to philosophy.

Michel Foucault once said: “what is interesting is always interconnection, not the primacy of this over that” (Foucault 2000, 362). In his essay Des Espace Autres (Of Other Spaces) Foucault (1967, para. 7) introduced the concept of the Heterotopia (Greek for ‘other place’), exploring how our lives are “governed by a certain number of [unalterable] oppositions”. These oppositions he sees as universally understood arising between different formats of spaces. Examples he gives are of between family and social spaces, or cultural spaces and useful spaces. Perhaps most significant for this work is the opposition he derives between private and public spaces (1967, para. 7).

The crux of his essay is simple: the spaces we occupy follow certain rules. That said, his definition of what space constitutes is rather broad and consequently perfect for our needs. He explains these spaces as sacred idealisations calling them heterotopias or placeless places because of their tendency to deviate from the norm. Foucault (1967, para. 9) goes on to assert that our lives are not in “voids” where the “individual and thing” may reside, rather the lives we live he contests are within sets of relations between unique moments we occupy. In his words these are “simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live” (1967, para. 13). My intention thus of utilising the concept of heterotopias here is to formulate a series of rules that the spaces defined in the above framework may enforce.

7.2.2.1 How are heterotopias formed?

In The Badlands of Modernity, Hetherington (2002) approaches concepts of societal modernity considering Foucault’s writings on power and politics. He expands on the notion of heterotopia as:

“Heterotopias are places of Otherness, whose Otherness is established through a relationship of difference with other sites, such that their presence either provides an unsettling of spatial and social relations or an alternative representation of spatial and social relations.” (Hetherington 2002, 8)

His definition explains how these spaces are created saying that they “bring together heterogeneous collections of unusual things” (Hetherington 2002, 43) as a deviation from the norm. More importantly his discussion focuses on how what matters in a heterotopia is seeing the relationship from an alternative perspective.

This approach makes it safe to imagine unique interactions that may exist within the overlaps of an inter-spatial interactivity model for IoT, as residing within a heterotopia—or a series of heterotopias. Hetherington (Hetherington 2002, 8) goes on to explain a grounding factor of these places of Otherness wherein they occupy “unsettling juxtapositions” of objects. Each contesting established orders of thought, creating alternative hierarchies of an unsettling nature as they “appear out of place” (2002, 50). This aspect allows us to view interactions in these spaces in a manner of urgency and thus challenging their meaningfulness towards the actors and the act.

Although the concept of heterotopia has most commonly been used to define alternate physical spaces as those referenced by Foucault himself—such as the cemetery, a festival, or the library—it also is used to define more abstract structures. Examples of abstracted spaces given by Foucault (1967, para. 30) are of the rug as a manner of garden, or a boat in water which he calls a “heterotopia par excellence”.

What this asserts is that heterotopia exhibit rules which define the actions that may take place within them. The insides/outsides of our defined spaces and objects in the altered model above may thus be further worked upon to exhibit their own unique rules if imagined as heterotopias. Rymarczuk and Derksen (2014, para. 7) discuss how the boat as heterotopia analogy may be seen as a reflection of cyberspace as a placeless place. They point this out from the fact that digital spaces often involve networks where terminals are connected to operate in a unified manner, even though being separate entities in different locales and times. They echo the point of view by Young (1998) where cyberspace can have further heterotopias residing within it (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 7). Furthermore, arguments have been presented suggesting smart cities (Wang 2017; Handlykken 2011) which are essentially IoT-enabled utopias, and the Internet (Warschauer 1995; B̆adulescu 2012) as modern imaginings of heterotopia.

7.2.2.2 Principles of Heterotopia in action

Along with defining this idea of heterotopia, Foucault (1967) established six principles to explain this further. As a philosopher historian Foucault’s explanation of heterotopia relates with society, power, and history. His broad approach at defining the characteristics of heterotopias make their concepts easily transferrable.

To begin he affirms that all cultures display the ability to create (or have created) heterotopias. The form of these are varied and depend on causal relationships to the space they inhabit, the culture they are tethered to, and other factors.

Second, society plays a role in altering “established heteortopias [to] change or adapt novel functions and new meanings” (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 5). Foucault (1967, para. 20) explains this with an example of the cemetery which evolved to be a city of its own from prior ideas of sacredness to a “dark resting place” for our loved ones.

Third, is how a single real space may be juxtaposed by several alternate spaces each with an apparent incompatibility to the original. Rymarczuk and Derksen (2014, para. 45) have expressed this to be a defining characteristic of heterotopias, wherein they allow a merger of spaces to exist; such as in our case, a merger of private/public or inside/outside.

The fourth principle establishes a concept of heterochronies, a thought that these places of Otherness are moments in time or using Foucault’s words “linked to slices of time” (Foucault 1967, para. 23). This means entering a heterotopia forces a break in traditional understandings of time. For instance, Foucault’s examples of when entering a cemetery, library, or museum, describe how time is constantly built up in these spaces. Time has no limit in them in how they horde objects and artefacts that are ‘timeless’ in nature.

Fifth, heterotopias have a manner of “opening and closing” allowing them to be at once isolated as well as be permeable (Foucault 1967, para. 26). A way of picturing this is through metaphorical gatekeepers entrusted with responsibilities to allow certain things to enter and exit the heterotopia. Digitally this can be imagined through payment, registration, and identification protocols.

Finally, heterotopias do not exist on their own and instead have a function that is related to what is around them. The definition Foucault (1967, para. 27) gives of this, is of seeing two extreme poles contesting each other in a bid to expose the space they occupy. Creating instead an illusory space that ironically defines the heterotopia as a compensation for the flaws of reality (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 6).

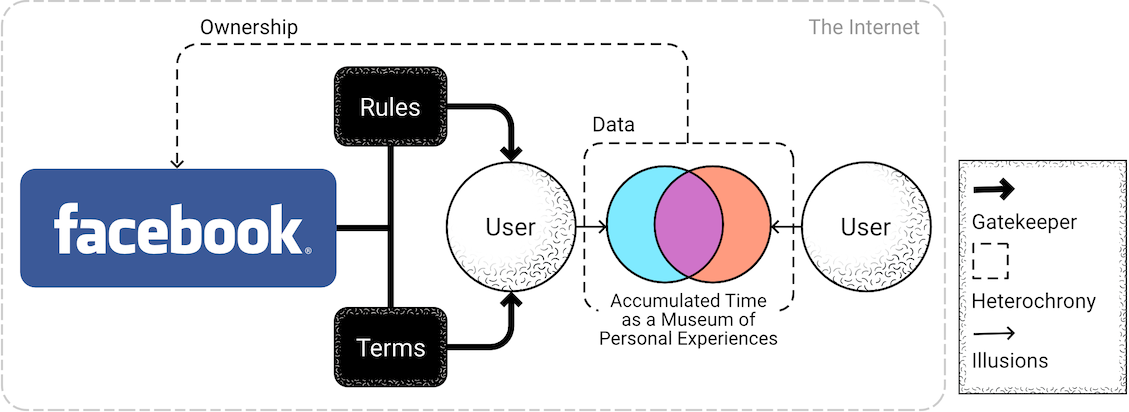

To shed light on this rather broad and vague final principle and accumulate the other principles in one example, Rymarczuk and Derksen (2014) present Facebook as a digital heterotopia. The online website/service requires actors—or in its case users—to follow certain rules of conduct. In order to immerse themselves in this digital world they must agree upon set terms through Facebook as the gatekeeper. This also strips away their claims to the information they provide. Rymarczuk and Derksen (2014, para. 12) critique this aspect of the service saying that leaving the space entirely is rather difficult. Since publication later updates of Facebook have added a deletion option though the design of the feature arguably discourages such activity. Furthermore, this does not remove already present interactions done with other users, such as posts or messages which essentially aligns to the fifth principle of heterotopias. Moving on they affirm that Facebook shows the “distinct regime of time” (2014, para. 15), that Foucault (1967, para. 24) describes in his fourth principle comparing it to museums that “accumulate time”. This makes Facebook a heterochrony akin to a library, but instead of books a library of personal moments and data. “Facebook collapses past life, present life and afterlife into something very other” (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 35).

Figure 7.4: The digital entity that is Facebook may be viewed as a heterotopia as it facilitates and oversees the accumulation of time through the lives and data of its users.

They converge on the third principle by explaining how Facebook views privacy, wherein the public domain is viewable to both Facebook’s owners and those constructing their social spheres. These create larger bubbles or networks, and though individuals are divided into seemingly personal spaces, what distinction should be present between private and public is blurred. This is because, the entity that is Facebook in its online presence as a whole “is not an undivided space” (Rymarczuk and Derksen 2014, para. 50). Finally, the sixth principle is a discourse on the illusion that Facebook gives of connectivity which they present in the manner of performance. An attempt to return power through “inauthenticity”, having its users “rejoice in the fact that it gives them the ability to present themselves to the world” (2014, para. 54). Facebook thus becomes a heterotopia existing within another heterotopia of the Internet (Fig. 7.4).

This adaptation of the principles of a heterotopia applied to a digital entity such as Facebook is a prime example of the above discussion of reframing digital spaces as possibly housing phenomenological insides and outsides. A spatial configuration enforced by heterotopic rules to guide the interactions possible within those spaces. With all of this information in hand I can now begin to craft a model for a philosophical view of IoT that inhibits the ability to see IoT interactions through a configuration of inter-spatiality.

7.3 Crafting a Model for a Philosophical View of IoT

The toolbox is now laid out and contains philosophies of phenomenology and an understanding of spatial theory combined with the ability to define spatial rules through heterotopias. In this section I will attempt to adapt all of these findings together to reimagine the above adaptation of Harman’s four-fold model. Just like when a personal diary becomes a heterotopic space of relevance to its owner, so too does a smart phone. And while online services such as Facebook can be seen as heterotopias, it is with the ability of ontography afforded by OOO that we can lay bare these interactions happening within the heterotopias of IoT. To explain this, I left out one example of Foucault’s heterotopias till the very end. It is the most compelling and the inspiration for this model. In it, Foucault describes the interaction with a mirror:

“The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface…a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself…But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am…The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.” (Foucault 1967, para. 12)

What Foucault poetically describes is a parallel space which appears to have utopic traits since you see yourself as an illusion. Essentially, the space of the mirror which involves the reflection exists because there is something in the space in front of the mirror. A second example he gives in this same note is of a telephone-line. When speaking onto a telephone we acknowledge the existence of the other through their voice-on-the-line. Though the other is not physically present with us, their voice is enough to give the illusion of their presence. The voice-on-the-line thus occupies a heterotopic space. In both examples, neither space can exist without the other. This can further be explored through IoT as a heterotopia when considering our devices. The act of seeing your activities on a smart phone, such as while using WhatsApp, can be presented as a parallel to the voice-on-the-line example.

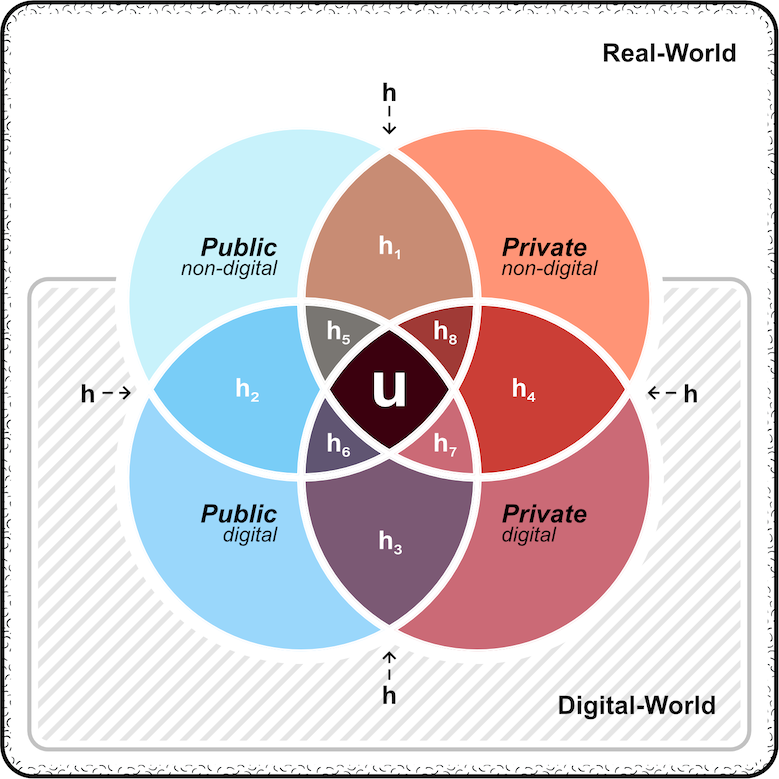

Figure 7.5: Model for a Philosophical View of IoT.

Thus, the following model now can be crafted (Fig. 7.5). It incorporates two spaces coexisting as one within the other each with its unique rules and regulations encompassing individual spheres of privacy and publicness. Our original adaptation of digital/non-digital objects/spaces is transformed to acknowledge the social nature of interactions occurring in these spaces by considering them as private/public or inside/outside bubbles. Though they still exist within the RW and DW larger ecology, they now converge to create overlaps collectively making a series of heterotopias. The overlaps created can be characterised as relating to Private–Non-Digital (PrND), Public–Non-Digital (PuND), Private–Digital (PrD), and Public–Digital (PuD) forming unique and albeit complex heterotopias (h1 through h8).

Private–Non-Digital (PrND): One of the two divisions of RW, it encompasses ideals and information that are most intimate to us forming our inherent acknowledgement of non-digital internal or private workings of spaces and objects within. For instance, the physical space of a bedroom could be considered a non-digital private space. Being a personal perspective it is hence of more importance to the individual to acknowledge it as such, but to function as a true ‘private’ it requires an understanding of a corresponding opposite.

Public–Non-Digital (PuND): Opposing general notions of privacy it defines the private as much as it defines itself. An open reality that exists around us, governed by culture, society, government, policy, to name a few. The public exists as a platform of interaction that is open and valid for all to interfere/intersect with. Carrying on the example of a home, a communal living room could be accepted as a non-digital public space, and in a larger perspective a park where one can be easily seen and interacted with.

Private–Digital (PrD): First of the two counterparts in DW, it incorporates rules that are defined by the individual to replicate their real notions of privacy. In Varnelis and Friedberg’s words, “the always-on, always-accessible network produces a broad set of changes to our concept of place” (Varnelis and Friedberg 2008, para. 1). They refer to the mobile phone as a “telecocoon” discussing how the device facilitates pseudo-private encounters in otherwise public spaces through distanced intimacy (2008, para. 22). Therefore, creating the counter existence of the private in DW. A personal smart phone can be considered as a private digital space within a non-digital object 35.

Public–Digital (PuD): Second of the two counterparts this facilitates the public sphere through digital interfaces. Interfaces here does not necessarily relate to physical interfaces such as smart phones rather those existing within the public ether. These are interactions that occur between digital objects within their digital spaces, think wireless transmission of data. The DW thus allows for a continuum of those interactions between PuND through to the digital. Alternatively, the inclusion of a non-digital object allows for an extension of this space into RW. As DW is a subset of RW this is anticipated. A television set can be seen as a digital public space experienced through RW.

Heterotopia 1 (h1): The first overlap to occur is between Private Non-Digital and Public spheres. Here the interactions are those that happen in our daily physical lives influenced by non-digital elements in the world around us. As an aid to understanding the concept better, I will be using an example of fitness tracking to illustrate the differences within the model. An actor could imagine the physical steps taken inside a building as being a non-digital private interaction that in truth is also a public interaction as the steps could be visible to others in the same non-digital space. This is because of the earlier configuration of private/public through inside/outside. Remember that public refers to the tangible concepts such as physicality whereas private refers to intangible hidden elements such as digital data. To the actant, walking alone indoors may appear as a private interaction though with the gatekeeper of this space being the building and not in control of the actant, this space becomes less private. By taking a step they have others potentially be aware of it. Furthermore, an amount of time is accumulated to take each step and observe it, hence the acts are heterochronic. Each step is taken has an illusion of displacement which, in this instance, conform to the laws of physics and subsequently remove one from their initial stance (standing or moving) towards another.

Heterotopia 2 (h2): Moving anti-clockwise around the model, the next overlap is seen between PrND and PrD. Using the same example of fitness tracking, this form can be seen when an actor uses a physical tracking device such as a Fitbit to represent real steps in an alternate state, in this case numeric data. Although the information is the same (they both represent physical steps) but due to the fact they are within two different spaces (RW and DW), they are visible in different ways. Variations of the Private clash together creating an alternate reality of privacy which exists only in DW, hence it is in many ways similar to the illusion in Foucault’s mirror; one version looks at the virtual version of themselves, and grounds the visibility of the other in their respective realms.

Heterotopia 3 (h3): Next, we see an overlap between PrD and PuD. The interaction here should abide primarily by rules in DW with little influence from RW. Continuing with our example, the steps saved to the fitness tracker are now allowed by the wearer to be stored on an online server. The reason this is a PuD interaction is because the server may be operated by other entities who could prescribe policies and regulations to oversee this information.

Heterotopia 4 (h4): The next overlap is between both iterations of Public. Many interactions tend to exist in this space which are free to access through open data creating a publicly viable connection between the non-digital and the digital. Looking back at the steps taken example, imagine a wearable device that doesn’t share data with its wearer, but instead saves it immediately to a public server. A service such as If This Then That (IFTTT)36 could then be used to parse this data and initiate some action. For example, the step data is sent from the device then parsed into an online spreadsheet. Another way of considering this is through the example of an IoT lightbulb. The bulb is connected to a digital interface allowing you to turn it on or off via a mobile device. By placing the bulb in a room that can be operated through a public link on Facebook, anyone with the link can access it digitally and change the status of this physical bulb. The bulb exists as a physical object and has a digital presence accessible through the mobile device making it exist there as an alternate of itself. When turning the bulb on from the mobile, there is no direct physical interaction being made with the bulb, yet a very physical alteration occurs in the state of the bulb wherein it turns on. This makes this interaction a very public one where even though physical contact is not happening a very visible physical change occurs.

Heterotopia 5 (h5): The inner overlaps of the model are where more complicated interactions begin to appear governed according to unique orders. The first of which occurs as a PrND–PrD–PuND interaction. As this occurs primarily in PrND it would be more influential, but the interaction would have traits of the other spheres. Let’s take a look at our steps being saved from our Fitbit. What if that data were to be synced with another device of a partner? This would allow them the ability to scroll through digital data shared with them and vice versa. Although the information here is present in different versions (real steps and numeric iterations) the presence of another individual and their physical device can be taken as being in both non-digital and digital spaces simultaneously.

Heterotopia 6 (h6): Here we see a PrD–PrND–PuD overlap with things primarily grounded by the PrD but influenced by others. This can be imagined very similar to our example in h5 by substituting the second device with a website where all data is synced and shared with a wider community. The use of social media can also be imagined here. The fitness tracker saves physical data it interacts with and sends that to a server, which subsequently interacts with social networks such as Facebook sharing the information publicly. The movement of this information from RW to DW and then again into DW but as a very different version of itself shows how simple data collection can be repurposed in different spaces exponentially. Every jump changing the data to reaffirm according to the nature of the other space it inhabits.

Heterotopia 7 (h7): In a PuD–PrD–PuND overlap a more digital approach of trust can be observed. The IFTTT protocol earlier imagined saving data on a spreadsheet can be reconsidered. This time though, instead of saving to a personal spreadsheet the data is visualised on a public device; perhaps on a digital display in an office. This display informs all employees about how many steps have been taken in the office, but only by the employees. Considerable trust must be given to the office servers with their personal data and devices to be able to accomplish this.

Heterotopia 8 (h8): Finally, in a PuND–PuD–PrND overlap one can see non-digital dominating the digital. A way to picture this interaction would be with a door that can monitor people going in and out of it using wearable RFID tags. The data is coming from a physical source and returning to a physical source by being displayed publicly. But what makes this unique from h7, is that here the data is taken directly from the physical source and not through any virtual channels. Alternatively, and to make it more interesting, the PuD can be a source of information that could be syncing an individual’s data according to their interaction with the door. Imagine a shoe with an RFID tag, it moves between the door and registers the wearer subsequently syncing fitness data that is tracked by the shoe. This in turn, is returned to physical output (like the same digital display), only this time through direct physical interaction.

The complex list of overlaps above, map out the many heterotopias occurring within an IoT-enabled space. Jumping between RW and DW, the information must morph and accommodate to the new rules and hierarchies the heterotopias enforce. This overlapping model leaves one space in the middle though, where much more complex interactions take place. Taking from the mirror analogy of a utopia this space has been marked u, and here is where a digital private-public yet simultaneously non-digital private-public interaction takes place.

To imagine this, deep levels of permission and trust need to be facilitated. That can only happen if the different interactions allow for major alterations in the nature of information handling. Therefore, some creativity is required. Imagine a scenario where your fitness data is tracked to your Fitbit. That in turn, sends data to a server which allows access to physical devices to relay that information when and where they wish. Now picture going into a gym and seeing a wall light up with your specific information. Your steps are being tracked and shared with you, but very openly. Others can see and possibly interact with it openly as well (perhaps via social media channels). Ignoring any personal concerns one might have with the public display of their gym performance, such an interaction can only take place when levels of permissions have been allowed over different spaces. These permissions will have to overlap with different policies, regulations, terms, and conditions, etc. By making this interaction between user-device-service-institute and so on, new heterotopias are dynamically created where the rules differ and thus the device must operate in that way. Any change happening in any of those rules reverberates through the entire constellation of tracking fitness through a Fitbit.

7.4 Discussion and Conclusion

The previously crafted model explores a kind-of spatial configuration for understanding the interactions that occur within IoT-enabled systems. It compares the phenomenology associated with OOO with spatial configurations coming from the field of human geography. It creates a series of spatial definitions that allow for interactions that occur within digital objects to be seen as phenomenological insides and outsides opening them up for scrutiny. It affords an open-ended approach at making visible the interactions of IoT through these philosophical concepts. That said, two questions can now be approached, (a) has this model answered the sub-question posited at the start, and (b) how has this model manifested playfulness within its design process?

Regarding the first question this model does not immediately answer that question but creates a trajectory towards answering it. This model in many ways extends the works of Boyd (2008) around concepts of “context collapse” (Marwick and Boyd 2011, 122) and “social-mediated publicness” (Baym and Boyd 2012, 322). Where her work focused on defining human interaction patterns occurring in social networks such as Twitter and Facebook, this model approaches a social networking of things by facilitating a similar discourse through heterotopias. Boyd’s (2008) concept of mediated publics comes from the notion that social media complicates and blurs audiences and ideas of publicness affording alterations to public engagement within those spaces. Her argument is that in order to navigate these mediated spaces we must alter our behaviours allowing new controls and skills to form.

The model approaches a similar construct by suggesting phenomenological object-spaces for digital objects and their interactions. These spaces are mediated just as Boyd’s view of social networks because through the object-oriented lens an object-geography is imagined. A social context collapse of digital/non-digital objects and their digital/non-digital spaces. To the digital objects the non-digital objects exist as equal to them on a level plane afforded by OOO. Because of this our interactions and the ways in which we must navigate them must be reimagined.

Furthermore, it also extends the on-going debate in understanding object-oriented-ness or the ‘insides’ of objects coming from previous chapters. Through their various efforts both Harman (2010c) and Bogost (2012) have debated the possibility of quasi-interactions and spaces exploring new theories of causation and imagining alternative perspectives of being. Though not encompassing all manners of objects and spaces, the carpentered model affords viewing the digital-objects through an object-oriented perspective.

Therefore, could this model highlight potential problematic effects within IoT? In some respects yes, through a playful appropriation of philosophical concepts using carpentry this model argues for an alternative perspective towards viewing IoT, and seeing the IoT object/device/thing as the ‘client’ in this design problem. “What does this IoT toaster want/need as a client?”, could be one way of viewing how this model helps understand the potential problematic effects within IoT because it attempts to lay bare an ontographical view of IoT interaction.

Regarding the later question of how a playful attitude has manifested here, this model as artefact takes vast liberties with how philosophical discourse is conducted. In many ways this entire manuscript does that, by equating concepts as things that have play imbued within them akin to Bogost’s (2016a) view of play existing within things. Rather than the things being toasters, cars, screwdrivers, grass, etc., here the things become philosophical concepts such as sensual, real, heterotopias, space, and so on to approach a phenomenological understanding relevant to this research. Granted no physical ‘thing’ has been ‘made’ here instead this chapter explores the making of a conceptual framework upon which further making may be conducted. In that sense playfulness as an attitude exists in the design process for seeing these philosophical concepts as possible play-things.

In Chapter 2 I expressed how while presenting a piece of my research at a conference to both philosophers and designers, I was met with a remark that this research would not bode well within philosophy circles but works for design. This model was that particular piece of research presented that day and remarked upon. It facilitates a designers playfulness with otherwise ominous philosophical constructs as if they were akin to Lego®.

It can be argued that this framework is still an anthropocentric perspective over an object-oriented one as I have used certain examples relating to human interaction in the model. The reason that was done was to create a relatable reference point for further non-human examples. True the heterotopias all exhibit information coming from gathered human related data (footsteps), it can still apply to non-human data. By substituting the Fitbit with a lightbulb existing on its own in its space a more object-oriented perspective may be achieved. The reason I keep the Fitbit example is because in the end we as humans share in these digital spaces as well. These objects are designed with the intention of being used by humans after all, so in a Catch-22-esque manner the human cannot be completely removed from this equation (at least not in this instance).

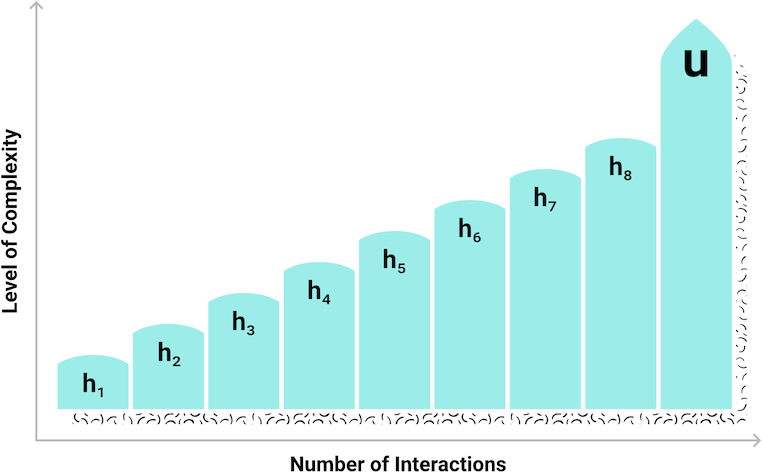

A design question this model may ask is whether it’s necessary for an interaction to occur when it does? Alternatively, it effectively allows a way of characterising digital and physical interactions as relations. These relations are explored through varying levels of permissions defined by their heterotopic natures. The carpentered model thus places a philosophical lens above IoT-enabled systems, revealing IoT in phenomenological terms through spatial theory. What can be noted here is that the closer one gets to the centre of this inter-spatial interactivity model, the greater the complexity of interactions occur (Fig. 7.6).

Figure 7.6: Interactions become more complex as we close in on the centre of the model.

The increased levels of complexity, which includes increasingly diffused relationships of trust, play a role in questioning the meaningfulness in how these interactions happen and are designed. The complexity that ensues from the ever-expanding interconnectivity of IoT means that a lot of information is either lost, ignored, or deliberately obfuscated. When various previously clear relationships of trust are being altered, is the interaction still worth it to the actor? Are there any measures that can be taken to renegotiate this trust, or, indicate that it has changed?

The social geography imagined of objects allows for a framework upon which discussions and further artefacts around the notion of mediated spatial configurations for IoT interactions may rest. The coming chapters attempt to utilise this framework to understand this notion further. For now, using the above model in conjunction with philosophical constructs such as OOO, a path for using philosophy as a potential tool to help in design research for IoT may be imagined by presenting a novel means of dissecting the inevitable messiness associated with digital and physical interactions.

References

The representation and usage of the four-fold model by Harman (2011b) here is done on a lower level understanding of object-oriented philosophy. This manuscript nor my expertise in philosophy are not sufficient to do justice to the amount of knowledge the four-fold model provides, and for that reason I will not be covering it in its entirety. For a detailed understanding of this model refer to works by Harman (2011b, 2018) the original source.↩︎

Occasionalism is a medieval Islamic philosophy, also present in early modern European works, which follows a rhetoric that the presence of God is a necessity for causation in order to allow two objects to interact with each other.↩︎

I should point out that private here does not refer to any information relating to the ‘privacy’ of an IoT-enabled network or device. True, privacy is a common topic discussed around IoT but here private is taken in a much broader sense to facilitate the crafting of an open-ended framework that fits our purposes.↩︎

Though prior published versions of the model explore it through digital/physical references, for simplicity I will not be referring to it as digital/physical here on as that brings about alternative definitions which I would like to avoid. The terminology was altered because this artefact deals with multiple terminologies intermingling, and the simpler I can keep it the better I believe. That said, most of the usage of non-digital objects/spaces to come in this text is in relation to physical spaces and objects.↩︎

Though it might sound strange to call a smart phone a ‘non-digital object’, that holds true to the framework established in this chapter. The smart phone enables interactions with the digital space, though itself it is an amalgamation of different non-digital materials such as glass, metal, silicone, plastics, etc. Furthermore, it exists not in the world of binary data that digital interactions concern with but in the non-digital world of atoms and molecules.↩︎

An online protocol that allows you to interlink IoT services and devices through simple algorithms or if-this-then-that statements.↩︎