Chapter 4 Being Things of the Internet

“The Internet does not exist…Because it has no shape. It has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time.”

— Excerpt from book jacket of The Internet does not exist edited by Arnada, Wood, and Vidokle (2015)

4.1 Introduction

Approaching a metaphorical understanding of IoT capable of discussing an objective perspective over a subjective human-centred one, requires expanding generalised models of HCD practice. Towards this end, this chapter attempts to lay a bedrock for understanding more-than humanness and accepting the possibility of an alternative perspective to IoT. This is done through an in-depth assessment of philosophical discourses around topics of Phenomenology, Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), and Speculative Realism moving towards a discussion on post-anthropocentric perspectives for design. As one of the two prongs of this thesis’ argument in playfulness and philosophy, the intention here is to present a philosophical discussion on viewing the world around us from the perspective of humans and subsequently non-humans to address a potential object-oriented vantage point capable of being utilised in further design application. To begin, it’s important to understand why this section on philosophy is needed.

4.1.1 A Philosophical Interlude

In episode sixteen of British comedy sitcom IT Crowd, Moss (Richard Ayoade) offers to lend Jen (Katherine Parkinson) a black box with a red flashing light on it saying, “This Jen, is the Internet.” Targeting her lack of computing knowledge, he explains how the box lacks any wires and is lightweight because the Internet is wireless and has no weight as everything is on the cloud. Moss’ colleague and friend Roy (Chris O’Dowd) objects to this but is later assured that the ‘Elders of the Internet’ agree with lending Jen the box. A cruel jest intended to embarrass Jen who, unbeknownst, presents the box to her peers. She then goes on to explain how if anything were to happen to it the world would collapse, falling into chaos. In true comedic fashion chaos does ensue after the box is destroyed in an accident, leaving both Moss and Roy looking over the spectacle befuddled.

This example, though an exaggeration, does a good job at playfully problematising the sense of magic a less informed person might associate with the Internet. As explored in the previous chapter, this ‘magic’ may be more readily acknowledged through IoT and applications of HCD. The existential nightmare of depicting the Internet as an IoT object itself aside, oddly enough the example also embodies (albeit comically) the disillusionment of one’s expectations with IoT coming from this lack of knowledge.

In the last chapter, I discussed problems that can arise from a user’s lack of knowledge attributed to practices of HCD, which attempt at presenting simplified experiences to human users of otherwise complex functions. This brings about an experience of IoT that lacks the sense of enchantment one anticipates of it and instead foregrounds its operational reality for users. The potential solution suggested is of a post-anthropocentric view of more-than humanness by acknowledging the presence of the things in IoT and seeing their independence and interdependence devoid of human involvement. This philosophical interlude thus attempts to present an understanding of what it means to be a thing in IoT, or an object of the Internet. This chapter in this regard, could be seen as a reflection of the previous one. Where that was about ‘seeing’ IoT objects, this is about ‘being’ one. In the coming chapters further light will be shed on the topic as we dive into different philosophical positions when and as they become necessary.

What is suggested here is the viewing of IoT through different lenses. Both IoT and design will be discussed again, only this time using a different lens representing philosophy. This reflection should solidify relationships between IoT and the idea of seeing through metaphor.

That said, throughout this chapter (and at points this thesis) I will be making use of philosophical thought experiments to elaborate certain concepts. Thought experiments are often used by philosophers to position theories using intuitive logic in a deductive process of reasoning (Ichikawa and Jarvis 2009, 222). Though arguments exist for and against the use of thought experiments as a method to posit theories (Cooper 2005; Bishop 1999), their use is commonplace in philosophy as they manage to ease the understanding of dense philosophical constructs.

As the purpose here is to build towards how design can fruitfully use philosophy as a like-tool in an ever-expanding metaphorical toolbox, the use of thought experiments allows for engaging in discussions around the various philosophical arguments and their relationship to design(ers). However, we need to begin this philosophical interlude one step at a time and start by asking a fundamental question around the existence of IoT objects: What is an object of the Internet?

4.2 Understanding Things on (and not on) the Internet

The opening quote of this chapter suggests the Internet does not exist because it lacks form or shape, although we claim to use it in different manners of communicating information. From sending private or public messages to switching on lights and interacting with satellites in space. So, what is it that we do when we say we are ‘online’, or, that something is connected to the Internet?

Perhaps one way to approach this is to first define the Internet. Different definitions exist ranging from the Internet as being a computational organism of interlinked computers processing information, to its impact in an anthropological context. The task of defining the Internet falls to understanding what the question is directed at (Abbate 2017). If we see the Internet from a technical standpoint alone as a technology, then yes, it is a network of interconnected computers working in tandem to create an experience of information exchange. However, at the same time the Internet is also a space for content creation and social activity, and as (Abbate 2017, 12) argue it acts as a localised experience meaning different things to different people.

How we define the Internet may also be an evolving definition coming from how media, politics, and society have shaped it through use (Lesage and Rinfret 2015; Morozov 2013). Flichy (2007, 2) dubs this the “Internet imaginaire” in how laws, values, and institutions are imagined for the Internet. He presents a cyclic model of how utopian ideals become the bedrock for new technological advancements. These don’t necessarily end up as initially imagined having to face compromises and constraints coming from present technologies and/or social ideologies. For instance, the idea of the Internet as an “information superhighway” was highly regarded and endorsed in the early 90s only to be slowly put aside as technology just wasn’t present at the time to imagine it (2007, 29). Though today this can be imagined with the height of advancements, it was short of a disillusionment a few decades ago.

Little argument exists against the Internet’s significance as a technology in the twenty-first century. However, Ropolyi (2018) suggests that the common definition of a network of computers must be put aside to truly accept what the Internet is—as not merely a connection of servers but a “highly complex artificial being with a mostly unknown nature” (2018, 40). Two concepts emerge here: seeing the Internet as a being, and the Internet (or its occupying things) having an ontology. The word ‘being’ here is not taken in its literal sense, but rather a phenomenological one. Approaching this would, in turn, define an ontological view of the Internet.

4.2.1 Phenomenologically speaking

Phenomenology is a dense philosophical movement dating back to the 18th century. Where the simplest definition of Phenomenology is the study of phenomena (Smith 2016, 1), it is important to note here that understanding of phenomena is a vast enterprise in philosophy. This text will not cover every aspect of the topic, rather, it aims to provide a core understanding to facilitate further discussion. Having said that, the definition of Phenomenology as a study of phenomena is better described through the notion of appearance (2016, 1). Not solely in the visual sense of something’s appearance, but rather the literal sense of appearing as; which could be taken from a variety of different sources (sound, memory, touch, opinion, etc.). This places Phenomenology, with the capital P, as a study of how things appear in their experience. Seeing the Internet as an evolving being of unknown nature as Ropolyi (2018, 40) suggests, means seeing it as a phenomenon that can only be understood through its experience. It is more than the sum of its parts, i.e., servers, terminals, computers, hard drives, radio frequencies, processors, etc. Making it possible to approach understanding the Internet, and the objects of the Internet, through Phenomenology.

4.2.1.1 Origins of the movement

Studies and observations in philosophy around the nature of being have been going on since Plato. These studies relate closely to the understanding of phenomenology. The word comes from the Greek phainomenon and logos, meaning appearance and reasoned inquiry respectively. A pre-history of the movement may be found in the works of 18th Century philosophers David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Georg Hegel, Franz Brentano, and others. Phenomenology started in a reaction to René Descartes infamous mind-body problem, which disconnected the mind (thought/thinking) from its extension (body/nature) allowing the mind to exist independently of the body (Smith 2016, 3). The true start of the movement though is accredited to Edmund Husserl in the 19th century, with Martin Heidegger positing the foundation for modern philosophies of phenomenology.

Descartes mind-body problem has been widely debated by scholars (Velmans 1998; Stewart and Mickunas 1974; Harman 2011b) and due to the convoluted nature of its discourse, I refrain from pushing forward into it as it crosses areas of metaphysics. That would be beyond the scope of this discussion (for the moment). As such, this text follows post-phenomenological views focusing on the works of Graham Harman who based his concepts from Heidegger’s writings. Before starting on that it would be beneficial to ground oneself in base phenomenological traditions, in order to situate the Internet and the objects of the Internet in a phenomenological context. This is because they set the stage for Harman’s ontological approach towards post-phenomenology, helping to ascertain why Harman’s views work for IoT and not others.

4.2.1.2 A brief overview of phenomenology

I will be aligning my arguments directly with either Heidegger or Husserl (both considered the strongest voices on the subject) in understanding phenomenology, mainly because (a) this thesis does not directly relate to their works, (b) these philosophers and their stances are effectively in opposition to each other, and (c) they both pursued different philosophical projects that don’t focus on capturing hidden qualities and causations which are of primary interest to this work. That said, they arguably both provide frameworks in which relations and qualities not apparent to the ‘naked’ eye are logically possible and can be phenomenologically inquired. This is why for their phenomenal work in establishing the foundational concepts used to develop Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) I will be paying homage in the coming text by briefly going over some of the core understandings of elements of their philosophy before focusing on Harman.

The phenomenology movement is often rooted to the famous quote by Husserl (2001, 2:168) of going “back to the ‘things themselves’”, in an attempt to decipher phenomena. As a core construct, Phenomenology rejects methods of science seeing them as being inadequate to answer questions around the nature of consciousness (Stewart and Mickunas 1974). The molecular structure of water might be able to construct various facets of water (such as viscosity, colour, etc.), but does not effectively describe one’s experience of water (feel, use, thirst, etc.). In this regard, phenomenologically appearance is dependent on experience, therefore, how the external world appears to us hinges on the experience directed towards us. For example, a tree seen outside my window is accepted by me as a tree because of the many factors that come into play when experiencing it (light, texture, colour, memory, time of day, etc.). All of which collectively create the phenomenon of experiencing and acknowledging the tree for what it is. Philosophically this is seen through constructs of intentionality, assumed by rejecting presuppositions that might influence any judgement of the experience, in a process known as phenomenological reduction (Smith 2016, 10).

This reduction brings about a keen interest in the definition of ‘Things’ in phenomenology. What constitutes a Thing depends on factors of intentionality and experience. Different definitions are presented over the course of the movement, but phenomenological problems are not obvious and simply being conscious of a thing cannot be enough to define it. Where Husserl’s view of phenomenology falls between empiricism and rationalism, it sees phenomenology as a descriptive rather than explanatory medium (Smith 2016, 25–26). My acknowledgement of the phenomenon of receiving a phone call comes from my inherent knowledge of my phone, the sound of my ringtone, the way sound travels in the air and my recognition of it as a telephone call. This does not in any way explain the phenomena of ‘receiving a phone call’ but rather describes it.

In contrast, Martin Heidegger (1985) rejects the Husserlian ‘neutral’ stance claiming it biased towards Cartesian philosophical traditions. His view of phenomenology is concerned instead with the “meaning of being” (M. Heidegger 1927, 227); in this respect, he refers to intelligibility. In essence, what he’s saying is that I can only make sense of something as a being or a Thing, once I am capable of understanding what it means to be that thing, making phenomenology an act of “systemic inquiry” (Smith 2016, 27). This approach of inquiring to the workings of something allows us to enter the debate of discovering what it means to be a Thing in the Internet.

The infamous tool-analysis by Martin Heidegger (1967) is oft cited around phenomenological discussions in OOO (Harman 2011b; Smith 2016; Merleau-Ponty 1996). The view is that things derive their meaning from their utility, with the famous example of a hammer whose existence only becomes apparent to us when it no longer is of use or when it cannot do what a hammer should. Its zuhandensein or readiness-to-hand and its vorhanden or present-at-hand, the apprehension that the world is made up of objects awaiting to be used. A third construct of Dasein (human existence) is also represented in Heidegger’s works and later expanded on by Harman’s (2011b) OOO which roughly translates to ‘being there in the moment’. Before continuing on this string of thought I would like to briefly step aside with a relevant example for IoT and phenomenological reduction in a thought experiment that should hopefully explain the connection here.

4.2.1.2.1 Thought Experiment: Seeing and Being Lightbulbs

Allow me to present an example of two lightbulbs operating in the same household. One is a regular lightbulb connected to a standard switch and wall socket that allows the flowing of electricity. The second is an IoT-enabled lightbulb also connected to a standard switch and wall socket but in this case the switch is kept on and it is interacted with through the Internet using a mobile application. To experience their respective phenomenon of ‘being’ lightbulbs Table 4.1 attempts conducting a manner of doing phenomenological research through a kind of auto-experience sampling of material object perspectives. A clearer defined usage of this often employed to communicate autobiographical first-person lived experiences (Finlay 2012).

Though in this thought experiment as neither lightbulb is truly ‘alive’, the auto-sampling is done from a human-user perspective mainly because certain experiences would be quite difficult if not impossible to define as not-a-lightbulb since I as a human have not lived as a lightbulb. Another concern is just how would the lightbulb communicate its experiences? In a language of objects? In Chapter 9 I attempt to explore this angle as a manner of agency more playfully and directly, but for now I will be restricting this thought experiment to as close an auto-experience sampling of a lightbulb as I can do myself while being not-a-lightbulb. Alternative methodologies such as thing ethnography, a non-anthropocentric means for “using things as co-ethnographers” (Giaccardi et al. 2016, 387), could also be employed to understand these perspectives. Though as thing ethnography is normally done using strategically placed cameras and microphones for extracting a thing-perspective, the approach I will be taking is of describing and comparing different traits between the two lightbulbs. This can be taken a step further by extracting specific data from a lightbulb at intervals akin to more common practices of experience sampling with humans. In this case the data could be conductivity, heat, lumens, intensity, time, etc to deduce phenomenological experiences unique to a lightbulb if one were to go that far.

For the purposes of this research, this level of detail is not needed. Furthermore, for simplicity sake we remove any functionality asides switching on as a lightbulb for the IoT-enabled counterpart. Our example does not look at the presence of electricity in the walls, the material of its surroundings, present/un-present information pertaining to the existence and production of electricity, the materials and workings of the mobile phone, or the wireless connectivity as those are considered givens and beyond current scope but can be expanded upon if need be.

| Regular Lightbulb | IoT Lightbulb |

|---|---|

| Appearance wise it is round, transparent, smooth, comprising of a number of materials including glass housing, a metal Edison cap, a coil/filament, and plastic connected to a socket in the wall. When turned on it shines bright. | Appearance wise it is round, transparent, smooth, comprising of a number of materials including glass housing, a metal Edison cap, a coil/filament, and plastic connected to a socket in the wall. When turned on it shines bright. |

| Sensory wise the glass feels hard yet smooth to touch when turned off, and warm and uncomfortable to touch when turned on. | Sensory wise the glass feels hard yet smooth to touch when turned off, and warm and uncomfortable to touch when turned on. |

| Reducing it further to its components we see its materials at rest and later heat up when flowing with electricity provided from the socket in the wall. | Reducing it further to its components we see its materials at rest and later heat up when flowing with electricity provided from the socket in the wall. Furthermore, it’s materials include silicone, electronic diodes, a radio transmitter for Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, a printed circuit board, electrolytic capacitors, polyester capacitors, inductors, and various microchips. |

| Functionality wise the light is powered through turning on a switch that feeds electricity through the wall into the wall socket where the bulb is fixed. Switching it in reverse cuts the flow of electricity and turns off the lightbulb. | Functionality wise the light is powered through a switch that feeds electricity through the wall into the wall socket where the bulb is fixed. It is turned on through a mobile application present externally on a smart phone. This in turn sends a wireless signal through the Internet to the bulb which is recognised on the network telling it to allow the flow of electricity from the wall socket to pass through the filament, turning on the bulb. This registers on the mobile application changing the status of the bulb to ‘ON’. Subsequently, turning the bulb off is done again through the mobile application that sends a wireless signal through the Internet to the bulb to cut the flow of electricity to the filament. |

When compared in this manner we see that to the user of both bulbs the experience is very similar and only changes once they acknowledge the different approach towards using the IoT bulb. Where the bulb differs is in representing the ‘magic’ of electricity through a smart phone application. Arguably one can say that to someone ignorant of how electricity works this magic is equally present when using a switch to turn on a regular lightbulb. That said, the difference in functionality remains irrespective. The association of unknown knowledge as to how the IoT bulb manages to turn on through smart phone sorcery is an acknowledgement of replicating experiences for end-users through HCD. They are intended to remain ‘magical’ whether you design for a regular bulb or an IoT-enabled bulb because the designer must facilitate ease of use which just so happens to appear as magic to some. In Heideggerian terms the relative ‘magic’ of an IoT lightbulb is more present-at-hand than ready-at-hand because people have yet to understand them.

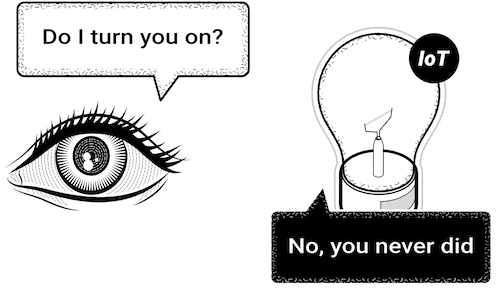

Table 4.1 describes both a regular and IoT bulb but from a human perspective because as not-a-lightbulb I am the one explaining my experience of being a lightbulb. This is coming from what little knowledge I have on the topic. There are questions that only a regular or an IoT lightbulb can truly answer. In the above example, there is no contest to what is happening when interacting with the regular bulb as a human. The question presented here is for the IoT bulb. When using it what am I interacting with, the bulb? Flowing electrons? Wireless interaction? The Internet? What am I experiencing?

It can be argued that as an end-user I am experiencing the same thing I would when using a regular lightbulb. But the IoT-enabled bulb adds this additional obfuscated layer of the Internet through wireless connectivity that the other bulb does not. If a regular bulb were to be turned on without my intervention with its switch, I may deduce it was done by someone else or possible rewiring unknown to me. But if that were to happen with the IoT bulb the answer is not as easy to discern, because wireless signals that go from a mobile phone to a physical device like a bulb need to bounce between numerous points which could be locally or globally situated and associated with a number of stakeholders and/or governing policies.

4.2.2 Towards an Object-Oriented Ontology

Returning to the previous discussion, when concerning the objects of the Internet the above thought experiment suggests that their existence becomes apparent to us (their users) once several ontological factors are addressed. Most notably it amounts to their utility, but also, an inherent understanding of what they entail. An IoT lightbulb allows me to brighten a room but also presents with it the ease of interaction that is not found in a regular lightbulb. It enhances a relationship between myself and my consumption of energy otherwise less apparent when using a non-IoT bulb. Furthermore, it also broadens the perspective of my energy usage in relation to my energy provider. It belongs to the world which I occupy (the physical room), but also to the world it operates in (the digital Internet). Its usage affirms a phenomenon of the Internet, which emerges through an experience of brightening a room without the use of a physical switch.

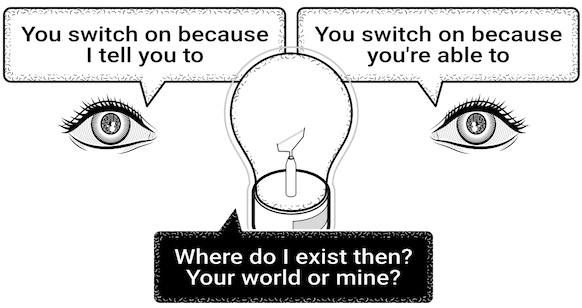

In this manner, the external-world (for a human-user or an IoT object) exists in either an objective perspective or a subjective one (Fig. 4.1). Either objects of the Internet exist because they are to be used by human-users, or they exist because they must function as they do, enacting their phenomena as independent entities.

Figure 4.1: The world that IoT objects exist in may either be defined subjectively (as in through a user’s perspective) or objectively (through the objects perspective). The former defines them by utility limiting their inherent potential.

This is the view shared by Correlationism, a concept introduced by Meillassoux (2010) in After Finitude. It asserts that things may only exist in relation to humans, making their subjectivity and objectivity intertwined, thus, inseparable to be analysed apart (Zahavi 2016, 294). Zahavi explains it as so:

“On this [correlationism’s] view, thought cannot get outside itself in order to compare the world as it is ‘in itself’ with the world as it is ‘for us’. Indeed, we can neither think nor grasp the ‘in itself’ in isolation from its relation to the subject, nor can we ever grasp a subject that would not always-already be related to an object.” (Zahavi 2016, 294)

It is a prickly concept to grasp, but the gist can be seen like so: our imagining of a tree cannot exist before us having experienced the tree as it is in relation to ourselves, therefore the tree cannot be thought of in isolation. In the previous thought experiment, I as not-a-lightbulb cannot remove myself from that notion to become a lightbulb unless I already was one or had experience of being a lightbulb. To overcome this, we need to change our viewpoint by examining a wider perspective.

4.2.2.1 Overmining and Undermining

In The Quadruple Object, Harman (2011b) describes a history of objects being shunned by philosophy and science in this manner as appearing naïve. Though phenomenology attempts to represent the presence of objects, it does so through idealism in his view. Harman (2011b, 11) quotes Berkeley’s famous maxim, “to be is to be perceived” as the idealistic stance towards viewing objects, whereby, one is in outright denial of the existence of an external world. Correlationism proposes an alternative view, yet, one that sees thinking and theory existing in tandem; inseparable from each other.

In essence, it discusses how an object is a metaphor drawn from everyday experience. Take for instance the Volkswagen Beetle. One may say the design of the car affords it the ability to be anthropomorphised. Its large headlights can be seen as eyes. The shape of its hood and bumper could be seen as a grin. This is only possible because our mind associates these anthropomorphic traits to the car. Its objective properties as a mode of transportation, and, its subjective image as a ‘living happy car’ are intertwined.

To Harman (2011b, 10), these different views of objects are seen as unit entities, which conceal and reveal their abilities to us. These hidden traits he claims have been historically ignored as unimportant to philosophical discourse by acts of “overmining” and “undermining”. Either objects are not fundamental since they are composed of far more detailed realities within them, such as atoms and quarks, making them “too shallow to be real” (undermined). Or, they are “too deep” a hypothesis, rendering them useless (overmined). In the latter view, objects are only important as manifestations in the mind, or through their interaction with other objects; the nail becomes important once the hammer connects with it, and vice versa.

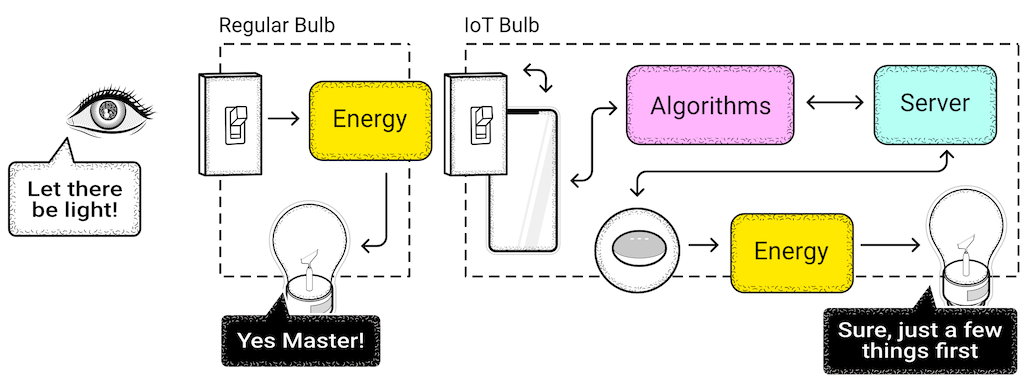

4.2.2.2 Exit human-experience

Irrespective of what view one takes, the fact remains that carrots, aeroplanes, snowflakes, and cats all exist and differ from each other. And each brings with them inherent interactions associated with not just human existence, but their own. What Husserl strayed from in his phenomenology were objects outside human experience. All discussion so far has been revolving around the human experience and related interactions. It should be noted, that an IoT lightbulb and a regular lightbulb cannot be considered the same object due to certain experiences of each. Though the outcome for both might seem similar (brightening of a room) and one may say the pressing of a digital button is akin to pressing a physical switch, the experience associated with turning on an IoT bulb and that of a regular bulb differ from each other on fundamental levels (Fig. 4.2):

Figure 4.2: A regular bulb and an IoT bulb though provide the same service they cannot be equated due to the unique underlying processes that each go through.

Much of this phenomenon is happening behind the apparent interaction of switching on the bulb. In the human experience, it is seen as a binary interaction, yet, the actual function is beyond. The object is thus entitled to a deeper existence apart from the human.

4.2.2.3 Enter the transcendental object

Kant’s Transcendental Idealism proposes a view where the human experience can be departed from, in theory (Harman 2018, 68; Stang 2018). I tread carefully here as the deeper I go in this topic, it breaks ground into deep metaphysics with arguments around morality, causality, space, and time; all of which we are better off avoiding for our discourse (for the moment). What should be noted is Kant’s view of ‘phenomena’ and ‘noumena’:

“[Kant] distinguishes in his philosophy between the visible phenomena of our conscious experience and what he calls the noumena. The phenomena are just what they sound like: everything that humans are able to encounter, perceive, use or think about…The noumena, by contrast, are things-in-themselves that we never experience directly, since we remain trapped in the conditions of human experience.” (Harman 2018, 67–68)

By considering an IoT lightbulb capable of undermining and overmining its traits, we associate more with this object of the Internet. We afford its existence on a plane of its own. One it has transcended to and shared (or not) with other such lightbulbs and IoT objects. Furthermore, this plane need not be part of our experiential phenomena, rather, it may operate on its own. The networks of heterogeneous interconnected objects of IoT discussed in the previous chapter, thus become the noumena spoken of here or the magic behind-the-scenes.

To surmise, to correctly understand the phenomenon of objects of the Internet (Things), operating in the Internet (being-in-the-world), through their non-human experience (noumena), we cannot rest on the idea of objects as naïve. Rather, understand how to view them as themselves and not mere actants in our reality. We must be able to see ‘out from within’.

4.2.2.4 Speculative Realism

No discussion around OOO is possible without mentioning its speculative realism roots. In April of 2007, during a conference at Goldsmiths College, University of London, philosophers Ray Brassier, Ian Hamilton Grant, Graham Harman, and Quentin Meillassoux coined the term Speculative Realism (SR) (Zahavi 2016, 294). It emerged as a reaction to correlationism which, as discussed, saw the external world as a “pseudo-problem” where we are either “always outside ourselves”, or, engaged in the world through “pre-theoretical” activities (Harman 2018, Introduction, para. 6). Shaviro (2014) explains SR as insisting upon an independence of the world, and the things that occupy the world from how we conceptualise them. It rejects prior philosophies around the structure of the world being dependent on our mind’s interaction with it, and, phenomenological assumptions of correspondence between self/world or subject/object.

People/humans are not the measure of all things to a speculative realist. To make this assertion, it is necessary to speculate about the alternative (Shaviro 2014, vol. 30, para. 2). This is an escape from inherent anthropocentrism to take in the existence of an alien non-human world.

Shaviro (2014) sees a sci-fi short story The Universe of Things by Gweneth Jones, as a compelling example of SR. In the story, aliens contact humans bringing with them their own objects which unlike human objects are intrinsically alive. They slither and creep and are not inanimate. The story encourages an alternative perspective of the “liveliness of objects” and their relation to us (2014, 30:3). It does this through the medium of speculating this alien encounter.

Though the philosophers who coined the term since have abandoned the rubric due to inconsistencies and biases, the use of SR as a label to identify opposition to correlationism is still useful (Zahavi 2016; Harman 2011b). Harman (2018, 57) since has encouraged a broader perspective of seeing things incorporating Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory that sees things-in-general as actants no different from us. This affords an expansive view of the world where human-engagement is overtaken by actor-engagement. Take the Volkswagen Beetle example, in this view beside it being a ‘happy living car’ with potential eyes and a face, it’s also an amalgamation of materials: leather, glass, aluminium, oil, rivets, circuit boards, silicon, a registration number, and so on. Collectively they create that specific Volkswagen Beetle, yet individually they retain their inherent uniqueness devoid of any association to the vehicle.

By viewing objects in this manner, he aims to enhance them to the levels of other non-objects around them effectively creating a consensus. Morton (2011, 165) describes this view as an attempt at reimagining realism in the wake of anti-realists. This viewpoint presents a case for an object-oriented world which exists besides our own (Harman 2018; Wolfendale 2014). Where lightbulbs, toasters, jackets, cars, etc. all reduce each other to readiness at hand when interacting 23. The earlier thought experiment attempted to reduce our lightbulbs in this manner to approach a similar object-oriented stance of causation and experience.

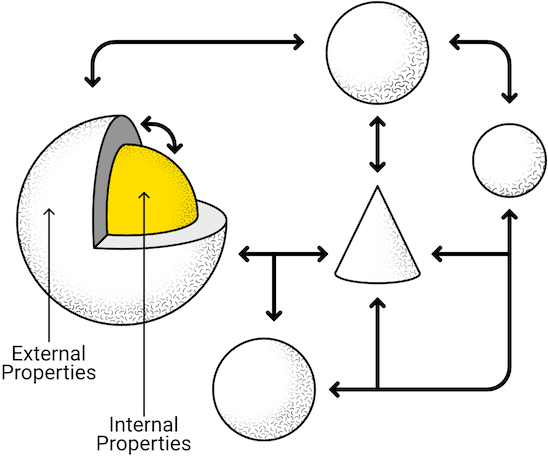

Figure 4.3: An IoT object may be considered present of their own accord as their existence does not rely on other IoT or non-IoT objects such as humans.

Hence, in an object-oriented world the title of Dasein can be presented to other objects as well (Fig. 4.3). After all, when I tap my smart phone to turn on the lights in the kitchen, my lightbulb does not interact with me it interacts with the smart phone or better yet radio signals. It is not aware of my existence (at least not in this instance), but rather the smart phones and the ether it interacts with. My interaction is with the glass surface and the sensitive diodes underneath. The bulb interacts in a non-physical digital space (the Internet) where photons fire away information. As in the above comparison with a regular bulb, the IoT bulbs function depends on the many interactions that occur between my tapping the smart phone and the bulb switching on. Thus, the nature of objects of the Internet is not dependent on our human presence or interaction. The bulb can still be turned on with a timer, or a sensor triggered by a cat. The design of these objects needs to be able to account for their non-naïve natures.

4.3 Object-Oriented Ontology

The above lengthy dive into the phenomenology of an object-oriented world was necessary to ground Harman’s theory of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO). As an abject refusal of correlationism, it takes on the mantle from where SR failed; to establish an unbiased form of realism. Dissecting the name, it can be defined as a study of the nature of objects from the perspective of the objects. Where it utilises elements of SR, it separates itself as well. Through the view of OOO, humans and non-humans are seen on equal footing. Having no precedence over the other each is equated as objects (Harman 2018, 9), in lieu of Levi Bryant’s notion of a “democracy of objects” (Bryant 2011, 19):

“Objects need not be natural, simple, or indestructible. Instead, objects will be defined only by their autonomous reality. They must be autonomous in two separate directions: emerging as something over and above their pieces, while also partly withholding themselves from relations with other entities.” (Harman 2011b, 19)

In OOO’s light, objects need not conform to any prejudiced view of what an ‘object’ is, and, alongside what might traditionally be thought of as objects, i.e. cupboards, teapots, the ocean, a history lecture, Saturn’s moon Titan, and Lahore are all considered objects. Much like the proposition by Latour (1994, 142) for a “parliament of things”, this view raises objects to the standard of “quasi-objects” (1994, 51). The constructed view of object-oriented-ness by Harman uses these ideologies and taps into Heidegger’s tool-analysis as a foundation (Bogost 2012; Harman 2011b), to explain how objects don’t need to relate through any human-use, but rather, any form of use including any format of inter-relational use.

Figure 4.4: An ontograph may be seen as the relationship between the properties of things with those of other things including internal and external properties which may interact both ways.

Harman presents these pairings of ontologies as ontographs (Harman 2011b, 2018) and their subsequent exploration as ontography (Fig. 4.4). The term he appropriates from a story by English writer M.R. James where a character assumes the position of ‘Professor of Ontography’. Bogost (2012, 36) later traces the term to a 1988 book The World View of Contemporary Physics by Richard F. Kitchener where it is defined as the description of the nature of things, or ontology. Where this definition of ontography does work for OOO, what I would rather keep is Harman’s comparative definition to Geography: “Rather than a geography dealing with stock natural characters such as forests and lakes, ontography maps the basic landmarks and fault lines in the universe of objects” (Harman 2011b, 125). It assumes an exploration of the rift between ontological polarities an object can take, or “vicarious causation” as articulated by Harman (2018, 150). Essentially creating miniature worlds full of relationships, perspectives, and possibilities an object may or may not incur.

To explain this, I present two examples: one set in the hypothetical science fiction world of British sitcom series Red Dwarf (1988), and the other set in our real-world smart objects:

The sci-fi setting of Red Dwarf is of a future interstellar mining vessel with a sole human occupant and several non-human occupants. These non-human occupants range from robots, software entities, a hologram human, and interactive appliances. Among these appliances is the Talkie Toaster. Designed in the fictional world it intended to provide light conversation during breakfast. The toaster though housed enough knowledge to enter into philosophical debates, creating a frustrating environment for the appliance and occupants. As the human occupant (and at times the non-human occupants) scorn the toaster for its fixation on toasted breakfast commodities, through OOO, the Talkie Toaster from Red Dwarf becomes on par with other characters in the series. An actor like all other actors in this play of existence.

Let’s now take for example the smart meter from the previous chapter discussed by J. G. Lindley and Coulton (2017). We’ve explored how IoT devices are both independent and inter-dependent. The smart meter is independent as a means for measuring energy usage but also relies on the interdependency of other entities in its constellation (energy provider, property owner, legislations, manufacturers software upgrades, etc.). Through OOO, each of these points on the constellation become individual objects collectively creating the smart meter, yet individually unique.

The two examples set a stage for two viewpoints of IoT. Where the former sees IoT objects as equal participants as their non-IoT cohabiters through playful storytelling, the latter expands on the idea of an IoT object to include a deeper existence. The equivalent of Talkie Toaster in our real world of smart objects is not capable of entering cohesive discussions with its users. That said, for IoT objects an object-oriented view means they may be imagined existing upon a plane equivalent to that of their users; the services they provide; the companies they benefit; the spaces they occupy; the affordances they provide, etc. Both Talkie Toaster and Lindley et al. constellation view, see smart objects as unique entities devoid of anthropocentric biases. Each creating their ontographical natures which can be examined by exploring the different polarities or viewpoints presented. The constellations approach allows for direct and indirect relationships of interactions to be viewed as unique ontographs or flat ontologies (J. G. Lindley, Coulton, and Akmal 2018).

4.4 Concluding on a post-anthropocentric perspective for Design

Where this discussion of OOO leads to is an imagining of the vicarious lives of equally animate and inanimate objects in our existence. Though such an imagining of the world from a non-human perspective presents its difficulties ([Lindley et al., 2019]), the premise provides a starting point to discuss a potential alternate view for designing in IoT; a view of the object as opposed to the user. In The Uncommon Life of Common Objects Busch (2005) narrates the unseen backgrounds of common objects around us, explaining how their design was influenced by the mundanity of everyday life. Her poetic approach towards household objects such as strollers and potato peelers evoke their mystique, suggesting that the objects around us have lives of their own signifying more than what one may assume their instrumental value is. This giving of life to an inanimate object may be contrarily seen as an anthropocentric approach of viewing life through the eyes of such objects. OOO though, suggests a post-anthropocentric view where life is a subjective definition employed by the object, not the human seeing the object. It is the life of the object itself, and what it sees.

J. Lindley, Coulton, and Alter (2019, 1191) discuss the potential for using a post-anthropocentric view as a way to view IoT networks as seen by IoT devices, by suggesting the presence of metaphorical “ghosts in the machine”. They hope to establish a platform for seeing interactions differently. Through OOO, we can map these connections between objects for the benefit of design. Bogost explains this through Harman’s example of a jigsaw puzzle rather fittingly:

“Things never really interact with one another, but fuse or connect in a conceptual fashion unrelated to consciousness. These means of interaction remain unknown—we can conclude only that some kind of proxy breaks the chasm and fuses the objects without actually fusing them. Harman uses the analogy of a jigsaw puzzle: ‘Instead of mimicking the original image, [it] is riddled with fissures and strategic overlaps that place everything in a new light.’ We understand relation by tracing the fissures.” (Bogost 2012, 11)

Talkie Toaster is shown in such a way of presenting the world from its own perspective. Creating new perceptions of interactions with a toaster, albeit within its fictional world all for comic relief. The tracing of fissures between it, its interactions, and those of its interdependencies, allow for a broader view of what a toaster is or could be. Those same interactions if presented within the confines of a design problem could offer an opportunity for intervention in the process of design for IoT objects, such as smart toasters, forks, bathtubs, apparel, etc.

I’m taken back to Rose’s quote: “Objects that anticipate their use; know when they’re needed” (Rose 2015, 111). This elegantly summarises the discussion of this chapter. Objects of the Internet anticipate their use, affording them a sense of presence. Their lives are full of experiences such as anticipating when they might be called to action. OOO allows for these vicarious lives of inanimate objects to be imagined. Rose’s quote poetically places objects in an arena where they have a sense of being, simultaneously, allowing us to view them ‘out from within’.

This topic is one that will recur in the following chapters. For now, I will pause the philosophy here to move towards establishing the methodologies of this research. With the case between SR and correlationism, one had to employ speculation to make sense. To approach the matter of IoT and Design through philosophy though, one needs to be playful. Having explained the philosophical foundation of this research, we can explore how to utilise philosophies such as OOO and design practice cohesively, by addressing the elephant in the room: design research.

References

Arguably Heidegger has spoken of nature independent of Dasein as well though where his explorations describe that, an ontology of existence must involve an understanding of Dasein’s interconnectedness with the “world human beings find themselves in” (DeLaFuente 2013, 5). Harman’s argument asserts removing the human element from the picture entirely to support a purely objective experience.↩︎