Chapter 2 Scaffolding

“Sometimes I’ll start a sentence, and I don't even know where it’s going. I just hope I find it along the way. Like an improv conversation. An improversation.”

— Michael Scott (played by Steve Carell) from The Office, Season 5 Episode 11

2.1 Introduction

The IoT has evolved much faster than my younger self could ever have imagined. I have a smart assistant in my house that my spouse and I play trivia with, which is in addition to its core household use as the timer for chips in the oven. The previous chapters’ stroll through the past only briefly mentioned one of the core aspects of this research: using philosophy to provide a design lens for my practice—at least where my playful attitude towards designing for IoT is of concern. Before touching on the philosophical aspect of this research though, this chapter explores some key questions I intend to address in this thesis. It also prepares a scaffolding for the methodologies I incorporate in my research journey.

This document does not take on the garb of a traditional doctoral research manuscript. In the coming text, a more detailed analysis of why this is the case will become clear. The journey of this research bends around different corners, stopping in different locations to collect knowledge before revealing its destination. Whilst the previous chapter explored the background this chapter explains the structure, defining why this work differs from more conventional doctoral research expressions. Subsequent chapters will delve deeper into philosophy, playfulness, design, and IoT.

First, any research conducted must ask key questions relating to its topic of concern. As discussed in the previous chapter, this research brings about a two pronged argument: the presence of playfulness and philosophy within a research through design approach towards IoT. In the process it brings together alternative speculative framings in an attempt at challenging orthodox HCD practices for the design of IoT systems. In this vein it also approaches problem spaces in light of prior research. Problems that could be attributed to established non-object-centred approaches such as HCD. The discussion invokes a philosophical carpentry of artefacts intended to act as playful appropriations of viewing IoT differently, hence the second prong of philosophy certainly must be part of the broad set question this research addresses. That said, as previously mentioned the discussion of manifesting a playful attitude within the design process is an important facet of this research as well, ergo restricting my research question towards IoT alone would limit the insights the research through design practice documented in this thesis reveals.

While this research is intended towards designers interested in practice-based methods towards problem solving IoT, its playful roots and attitude are what truly drive the discussion forward. IoT here was the subject of research coming from PETRAS and acts as the locus of this discourse. It could just as well be substituted for other topics that this playful practice-based approach may be equally helpful in facilitating. Therefore, the broad question this research intends to answer becomes:

Q. How does a playful research through design process manifest itself within performing philosophical carpentry to create artefacts to be experienced by a diverse audience?

This broad question sets the agenda for conducting the explorative design research considered in this thesis. Specific sub-questions emerge through the course of the work which attempt to address the different areas of interest in coming chapters. This is done through a practice-based exploratory approach at problem solving key areas of focus in IoT. In the process I present an approach of conducting philosophical inquiry through a metaphorical carpentry. As the main philosophy explored in this thesis is Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) which argues for a more-than human non-anthropocentric world view—further details in Chapter 4—this thesis may also be seen as a way of presenting carpentry as a means to answer the core question of this research into manifesting playfulness within design processes towards a more-than human world view. The sub-questions in this regard are:

Is it possible to highlight potential problematic effects emanating off IoT products and services approaches through an object-oriented lens?

How does an attitude of playfulness occur in this research through design activity?

How can the philosophical foundations of a proposed non-anthropocentric IoT be manifested in RtD artefacts?

Each sub-question is addressed in varying degrees in the coming chapters with some presenting their own internal questions for the designed artefacts. It should be noted here that though philosophy is mentioned in the questions, this research is not ‘on’ philosophy rather it uses philosophical discourse as a lens for the design processes. It represents an attempt at presenting a playful attitude towards design with a focus on designing for IoT in a more-than human world-view. Putting these core research questions aside for the moment I will now address why this research is structured the way it is.

2.2 Steppingstones into post-modern humanities

A thesis or dissertation of academic stature requires the grounding of any conceptual discourse in established ideas from a scholarly community. These bodies of work most commonly take on the form of a review of literature in subsequently related, and at times disparate, fields of research. The generally accepted definition of research is the crafting of knowledge through systemic investigation, where knowledge is generated by the combination of information and analysis. Webster and Watson (2002, xiii) believe, that the efficacy of a review establishes strong foundations for the “advancing of knowledge”. Facilitating the development of theory and unearthing hidden avenues of further research. Quoting Dudley-Evans (1999) and Thompson (1999) on the variations in approaches towards theses and dissertations, Paltridge (2002, 132) examines the differences between conventional methods of doctoral thesis writing and their real-world practice. As a result, the traditional approach to structuring a thesis has evolved to incorporate an array of approaches; some of which Paltridge explores in his paper. He defines the traditional pattern as a “simple” one, involving a “macro-structure” taking on a generic format of an introduction followed by a literature review, a methodology, ending in findings, and a conclusion as the result of some discussion.

Where this defines his view of a “traditional pattern” in thesis writing, a more complex structure he claims is required for the study of more than one topic (Paltridge 2002, 132). Other sources bring to light alternate methods of thesis writing, which include a topical approach (Dudley-Evans 1999), and a thesis as a collection of published research articles (Dong 1998). Where the former bifurcates a topic into relevant subtopics, the latter is a more audience-centric approach meant for experts in a field (Paltridge 2002, 132).

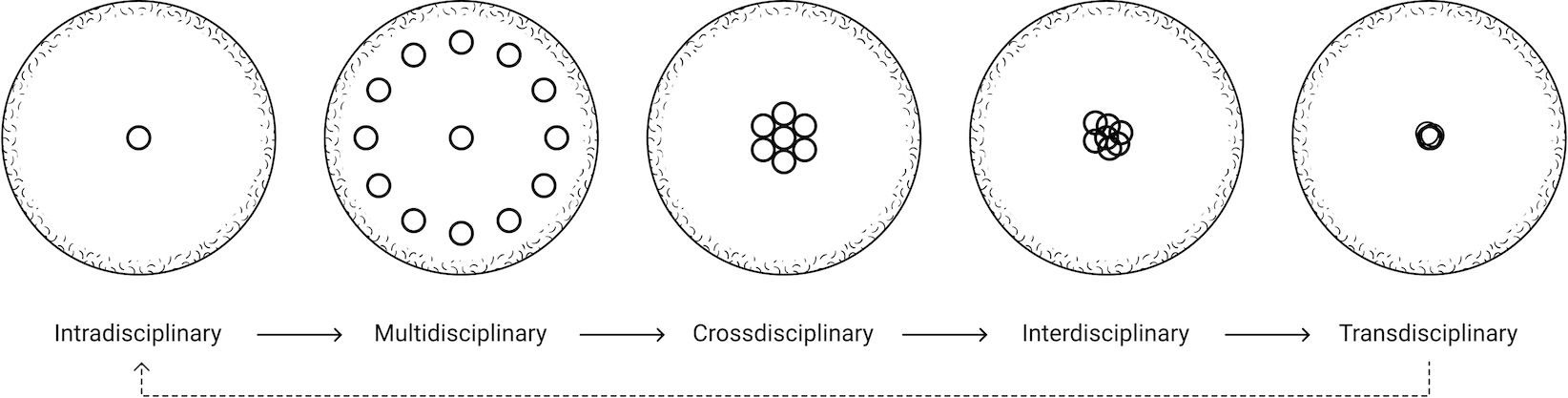

Figure 2.1: Jensenius (2012) presents the evolution of research approaches which may be visualised as moving away from conventional means of research towards transdisciplinary perspectives.

Though research articles of the social sciences often conform to standards established by scientific research, Stember (1991) points out the influence of academic disciplines in research and calls for advancement in social sciences through an interdisciplinary research approach. Gibbons et al. (1994, 1–2) see this as a transition of knowledge production from Mode 1 to Mode 2, where the former equates to traditional understandings of research and knowledge production, i.e. scientific research or Newtonian models, the latter approaches ideals of trans-disciplinarity. Appropriating Zeigler’s 1990 model for differentiating between research methods, in an attempt to understand this Jensenius (2012) presents a broader model that offers an evolutionary view of research approaches (Fig. 2.1). In this model, five major modes of research are plotted:

Intradisciplinary when working within a single discipline with no overlaps

Multidisciplinary when collaborating between different disciplines, such as the invention of the defibrillator which can be seen as a combination of biology, chemistry, and electric engineering

Crossdisciplinary when viewing a discipline from the perspective of another, e.g. genetics

Interdisciplinary when integrating knowledge from different disciplines through synthesis, such as how literature is a synthesis of history, anthropology, science, etc.

Transdisciplinary when creating a unity of intellectual frameworks beyond disciplinary perspectives, e.g. studies in sustainability often transcend knowledge from areas of concern

Presenting these major modalities of research in this manner reveals an evolution of research practice moving away from conventional approaches. On this, Hodge (1995, 35) presents an argument for a “revolution” in social science research, which he calls the “New Humanities” or “Post-modern Humanities”. In his text he speaks of the trans-disciplinary nature of post-modern humanities as abnormalities to be studied and explored encouraging avant-garde approaches towards knowledge production.

2.2.1 Transdisciplinary Design Research

In the context of design Boradkar (2010, 281) argues that design problems posit unique challenges that require “unique set of tools” often of an interdisciplinary capacity. In order to tackle these challenges he echoes other scholars in affirming that design as an independent discipline must “enrich itself in transdisciplinary engagements” (2010, 282). Friedman (2000, 39) motions that design as a discipline exists in the “intersection of several large fields”. As an example of this Boradkar (2017, 462) explains how web and mobile application designers often require an understanding of computer programming alongside graphical design knowledge. This presents two forms of design which Mitcham (1994, 461) refers to as engineering-design and artistic-design respectively, each requiring different levels of mastery.

Quoting Klein (1990), Boradkar (2017, 462) continues to describe design practice as “transdisciplinary problem solving” focusing on present research questions over discipline. This research attempts to approach transdisciplinary problem solving using a Research through Design (RtD) methodology which I explore in detail in Chapter 5.

Furthering the point of generating transcendent knowledge, studies involving research around science topics such as engineering, chemistry, and mathematics could justify a regimented approach. However, as this research involves the interactions of elements within and beyond logical science, it plays with the ideas of logic using philosophical thought experiments. Meaning to interweave itself within the fabric of human and non-human interaction. The attitude of playfulness that this research proposes acts as a way to facilitate this weave through the vehicle of philosophical inquiry into alternative perspectives of IoT. The methodology used here is part natural science, and part social science.

To bring this further into perspective metaphor is elaborately employed. In After Method Law (2004) discusses alternative approaches to considering research methods. He equates the world to a “set of possibly discoverable processes” (2004, 9), encouraging researchers to attempt to bridge research through “method assemblages” (2004, 13). These assemblages create what he calls a “hinterland” of relations between methods (2004, 13). Giving an example of how philosopher Bruno Latour’s examining of the world of Salk Institute’s endocrinologists became the basis for a new field of study known today as the ethnography of science, he explains how a philosopher with no prior background in science can do this by subverting method into a definition that is more generous and looser to conventional understandings. To this Law argues that “[Social] science should also be trying to make and know realities that are vague and indefinite because much of the world is enacted in that way” (2004, 14).

As this work defines itself within the boundaries of design research using iterative methodologies—namely RtD and speculative design—it raises a connection between design and social sciences. An association which began in the 1980’s as a design-driven experiment crafting what we today know as user-centred design (E. B.-N. Sanders 2002, 1). Adding to that is the on-going attitude of playfulness and rhetoric of philosophy as a driving force for designing in a certain manner and intention that this research advocates. This places design research on par with the likes of social sciences such as psychology, geography, history, and anthropology among others; all having their own established formats of research. Although fundamentally being research into the IoT, it requires an understanding of technological processes and knowledge representation related to the different areas of concern.

2.2.2 Crafting Trandisciplinary Assemblages

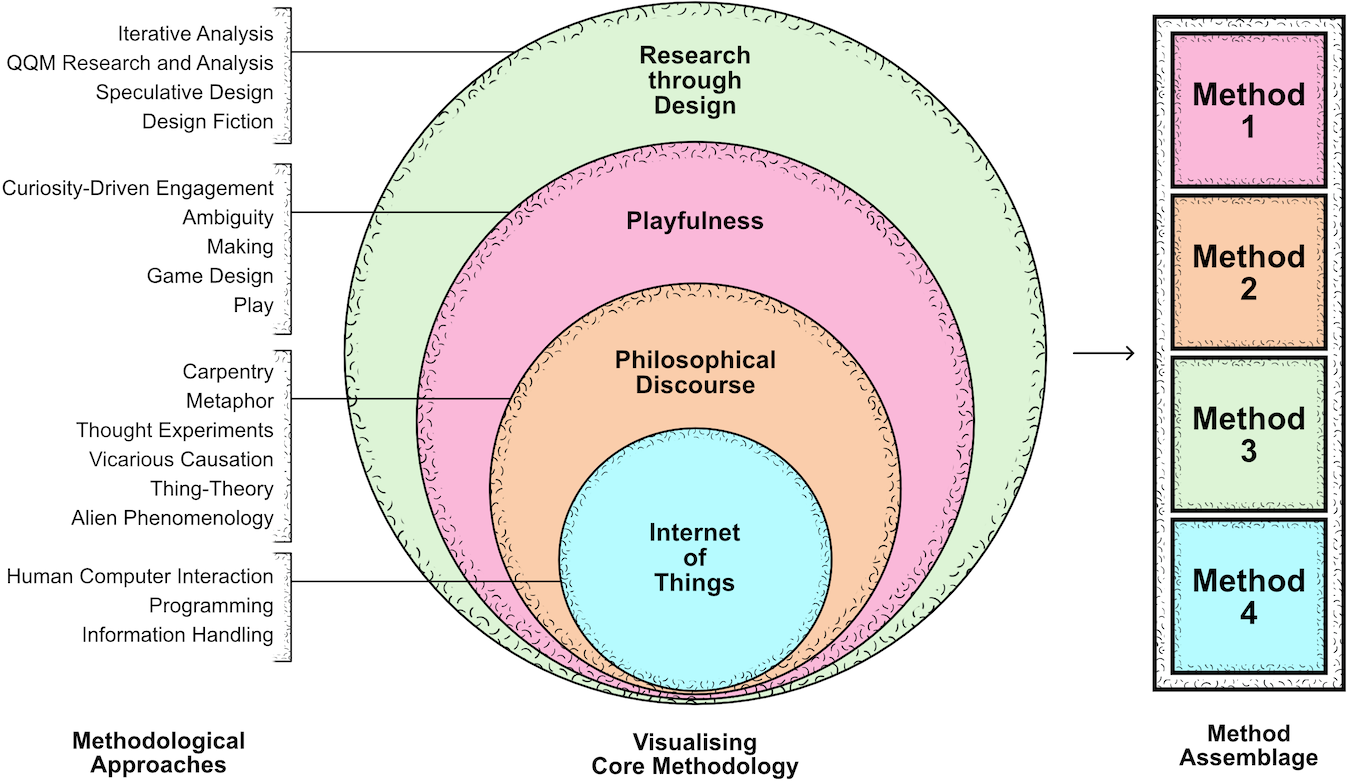

When seen in this manner, this research falls beyond the scope of the formulaic traditional thesis approaches defined by Paltridge (2002). Whilst including topics which have established approaches towards academic writing such as philosophy and writing for computer engineering subjects related to IoT research, the way this work utilises these disciplines happens in a manner of equating them to tools found in a toolbox. This all places this research in a spectrum of interdisciplinary studies bordering on the transdisciplinary, akin to the method assemblages discussed by Law (2004). Through this idea of transcendent knowledge, I present the formulation of unique ‘engines’ for transdisciplinary design research (Fig. 2.2).

Figure 2.2: The knowledge generated through designed artefacts in this thesis comes from assembling methodological approaches present within the concepts this research concerns with. In doing so it approaches a manner of transcending knowledge between disciplines through design.

In the coming chapters, each of the individual parts of this engine are discussed in detail and explored from the vantage point of design research. Each provides a unique perspective towards the challenges of designing for IoT products and services and in turn articulates unique knowledge production. Since this research argues for an objective view at orthodox design practices such as HCD it becomes necessary to include philosophical perspectives such as object-oriented philosophy that may offer alternate perspectives. Playfulness here is an ever present attitude within the designer and the process that supports the crafting of unique explorative design artefacts to indulge the philosophical views intended to be explored ahead. And finally, a practice-based RtD approach ensures an iterative exploration of the design problem that may be equal parts explorative and critical in nature.

2.2.3 Transcending method through Design

While presenting a paper involving one of the artefacts from this research at DRS2018, the ensuing discussion raised a point to how the practical manner of research would not fit within the traditions of the discipline of philosophy. However, the consensus was that it fit well within the boundaries of design due to the freedom available in the discipline. Lee and Lee (2019) map the characteristics of design research within the humanities for inter and cross-disciplinary research. They conclude that understanding the implications and applications of design within other disciplines may help in developing the field of Design. E. B.-N. Sanders (2002, 6) presents the argument of designers and design researchers, specifically social scientists working in conjunction with design and/or designers, as being interdependent. The appropriated freedom in design as a discipline for knowledge generation thus comes from this interdependence. As such, this research aspires to become transdisciplinary considering approximations by Hodge (1995) and the notion of method assemblages from Law (2004). By moving between the hinterland of relations connecting interdisciplinary research, this work attempts at expanding on established models of design for IoT to encourage potential new directions. These unique engines for research are comprised of different combinations of methods here on considered ‘tools’ in a metaphorical toolbox.

This is not equating them as design tools meant to be used in that fashion, rather it is a play on the word ‘tool’ from ‘toolbox’. Within each toolbox are the assemblages of different concepts coming from different disciplines used in the design process of each artefact.

Therefore, I do not see imperative in allowing this thesis to conform to the generic format of a postdoctoral manuscript. The elements required for a document of this calibre will all be present: a review of relevant literature; intent of research; methodology; findings; and discussion to take away at the end. But due to the nature of the study and its involvement of different research topics on a transdisciplinary platform, the potential for a modification of the standard model of a postdoctoral thesis presents itself. Another way of looking at it is this research attempts to transcend knowledge between areas of philosophy, design, playfulness, and technology, and might feel odd in places.

2.3 How to use this Thesis

By jumping between different topics of concern this research risks raising levels of confusion. Thus, rather than have a larger review of literature presented in one chapter in the start, references to literature are placed appropriately throughout the text. An introductory review will be presented in the initial chapters, but each chapter will also have its pieces of reviewed literature brought up on an as-per-need basis. This should help alleviate any confusion, allowing readers to avoid jumping back chapters to reacquaint themselves with topics. It should also help in establishing a cohesive discourse throughout.

The previous chapter was a brief dive into some background in myself and how this work came about. This chapter provided a scaffolding for why this document is laid out in this manner along with the core questions this thesis aims to address. The next few chapters may be viewed as a mise en place for the coming artefacts designed as part of this research. My intention with them is to incorporate an understanding of seeing, being, and designing things of IoT in order to grasp the foundations of this research. Here is what can be expected ahead:

Chapter 3 starts us off by introducing our focal point of IoT and how it is seen in a general sense. I present a case for and against general approaches towards design in IoT. Supported by a review of relevant literature I lay a foundation for our discussion around technology in this research. Following it up with why design for IoT matters, challenges currently at play, and how metaphor may be an ally in seeing IoT. This chapter incorporates our first step at seeing through an alternative lens.

Chapter 4 attempts to unravel the dense philosophical concepts this thesis utilizes in the coming designed artefacts. It covers the core philosophy of phenomenology that is discussed throughout. Building towards the main discussion of how things in IoT exist I argue for how design approaches can see them through an object-oriented perspective of simulating agency within things. This expands upon notions of alternative perspectives towards viewing technology from Chapter 4.

Chapter 5 is the first of two chapters on used methods and core approaches in this research. It dives into an exploration of design research as a methodology. Here I approach the idea of an iterative design perspective of creating artefacts for this design research through an ideology of Research through Design (RtD).

Chapter 6 explores the broader attitude of playfulness this research advocates comparing it to decision making and design processes. Here I take on the idea of playfulness as an asset for design research, making a connection between disciplines of design and the act of play through curiosity-driven engagement. This is also where I introduce the concept of philosophical carpentry as a way of playfully approaching design research and philosophy to form the method assemblage toolboxes explored in Chapter 2.

Chapter 7 through to Chapter 9 introduce the research through design aspect of this thesis and each present a different artefact intended to enact philosophy. Starting with a way of defining a model for a philosophical perspective of IoT, using play to prod and poke at the design of IoT systems. Each chapter in this series is accompanied by different philosophical concepts and design approaches used in its metaphorical toolbox with findings and insights. Chapter 7 introduces a core framework for viewing interactions occurring in IoT through philosophy. This framework is then carried on to subsequent chapters in an attempt to explore it further. In this regard Chapter 8 walks through the process of designing a board game based on the framework. It defines the iterative process and design decisions made in designing the Internet of Things Board Game with a discussion into the pitfalls and compromises undergone in the process. Finally, in this series Chapter 9 dives into a deeper exploration of the framework enforcing a more direct relation with the philosophical discourse defined in this research through imaging the personal lives of IoT objects using Tarot.

Chapter 10 brings about the final section of this thesis, with a discussion into the implications of carpentry for design research through findings and experiences, and a discussion into manifesting an attitude of playfulness within the design process. It is accompanied by a discourse into the future potential for research in this manner, before rounding up the conclusions of this research.