Chapter 5 Design Research

“A designer is a thinker whose job it is to move from thought to action.”

— Friedman (2000, 37)

5.1 Introduction

The previous chapters have slowly been setting the foundations of this thesis. Starting with what it means to have things around us that connect to the Internet our discussion moved on towards embodying these objects to ‘see through their eyes’, so to speak. In order to explore these concepts through design this and the coming chapter define the methodologies used throughout this research. Since the concerns of this research are to do with alternative approaches to design and incorporates tangential topics of a transdisciplinary nature, a unique methodological approach capable of justifying the use of philosophy for design of IoT must be developed. As such this is developed across the subsequent two chapters, the first deals with the overarching design approach and the second with accompanying internal methodologies, linkages, and manifested attitude of playfulness. What I intend to do is present a combined methodological framework at the end of this section that inherits attributes from its constituent methodologies and concepts.

This chapter discusses iterative Research through Design (RtD) as an overarching methodology used throughout this research. The topic of design appears in various forms in this manuscript, mostly as crafted prototypes of ideas (physical, digital, or on paper) but also in the manner of its discourse. As such, I hope that this research may feed the greater knowledge of practice-based design research. In Chapter 1, I mentioned how doing an MA in Design Management opened me up to the potential of design research. It also reminded me how much I missed practising art and design in general. The presence of practice-based research is thus very important to me and contributed to the decisions made in the course of this work.

A number of different design approaches are utilised in the coming chapters, which is why the activities mentioned here on represent a predominant RtD ideology. It also presents the argument both for and against the suggestion of RtD as a methodology, which I go into more detail later. This is why even though it is present in the methodologies section of my research, I refer to it as an ideology instead as I see it as an overarching structure to support further methodologies that I use in my research owing to the playful attitude towards research I present throughout. These intercept design problems using creative and philosophical appropriations of designed artefacts.

Thus, to ease the discussion further, this section is divided into two chapters. The first addresses approaches for design research moving towards the application of RtD as a methodology in this manuscript with a review of relevant literature. The second, explores accompanying methods to add to a design and philosophy toolkit of sorts used in chapters discussing my practice. For now, in this chapter I intend to lay out why RtD is the methodological framework of this research. For that I will focus my discussion on doing design research for solving wicked problems such as those associated with IoT.

5.2 Doing Design Research

When considering a starting point for the discussion of design research, I realised it to be the most challenging aspect of compiling this document. Ironic as it is, the question of what design research is never truly came up while doing a PhD in Design. It was inherently understood. Perhaps this has to do with the fact that one explores these notions earlier on in their academic life. I touched upon it in my MA, but the idea ingrained in my mind then was a definition of design research specific to Design Management. Since then my understanding of what is research, design, and design research have evolved. The term ‘design research’ is often used in industry practice and academia alike. The following account of design research is thus influenced by my earlier understandings of design, and a new founded knowledge into the greater expanse of design research as a discipline. So where does one begin when discussing what is design research?

Edelson (2002, 106) describe the role of a design researcher as one who passes through “iterative cycles of design and implementation”, with the intent of collecting and processing data to generate information. This collection of information is sifted and prodded to form hypotheses that further reflect upon crafting theories and artefacts, which in turn, are presented as outcomes of a ‘design experience’. Faste and Faste (2012) attempt to demystify the usage of the term ‘design research’, to describe the myriad viewpoints that emerge while practising design in varying capacities. These include but are not limited to the various philosophies, methods, or approaches one may adopt or unearth while ‘designing’.

The term is formed by combining two very distinct words—design and research—both having their own definitions. Where the core idea behind both is the generation of new or refined knowledge in some form, there is a general differentiation between the two that has become accepted over time. I will begin by defining what design is in the context of this research and move on from there.

5.2.1 Defining Design

Design is a word used to express a multitude of meanings stemming from its nature in the English language as at times being a verb (to design), a noun (a design), and an adjective (by design) (Glanville 1999; Julier 2013; Lawson 1990; Frankel and Racine 2010). The term encompasses a broad spectrum of disciplines that associate different meaning to it according to its varying nature, from being a process or a tangible outcome of a process (Cooper and Press 1995; Friedman 2000), to a psychological perspective taken by an individual (J. C. Thomas and Carroll 1979).

Friedman (2000, 32) traces the creation of design knowledge throughout history as a systemic evolution of toolmaking dating back to homo habilis. This view of the “acts of design” (2000, 34) embodies the rich heritage of craft making, which emerged out of a need for tools in human history. It also places design as both a vocation of trades and crafts, as well as a contemporary profession having evolved over centuries.

He presents a taxonomy of design knowledge as seen through core domains of inquiry that a designer is faced with. These include various skills for learning and leading, a view of the world we occupy, the artefact of intention, and knowledge of the environment and surroundings (Friedman 1992). Collectively this taxonomy establishes a range of activities designers intend to partake in. What he refers to is how fundamentally design occupies multiple disciplines, thus, having designers require a breadth of knowledge to exercise design practice.

Cooper and Press (1995) attempt to refine the many definitions of design into different perspectives and core functions established in industry and society. This refinement sees design as a form of modern art, a problem-solving activity, an act for manifesting creative thought, a family of professions that include its craft heritage, an industry in its own right, and above all a process for accomplishing particular goals.

For the intentions of this work two definitions of design will be built upon. Design here is both a process and an act of problem-solving. It is together used to establish a structure for discourse, as well as a means of manifesting creative thought. The act of designing is important here due to the practice-based nature of this research. There are elements where design is used as a craft for aesthetic purposes, but at the same time, these don’t impair the quality of design as a process in achieving a specific goal. These two aspects of design relate to the core ideology of RtD present throughout this work.

5.2.1.1 Design as a problem-solving activity

Don A. Norman (2002) view of design may be summed up as a process that makes the world more usable; or not if that is the desire. Though the general consensus is that a designed object is intended to present a level of craftsmanship above similar less-designed objects, what Norman suggests is that design inherently possesses the ability to craft usability. Implying designed objects intend to do something—as in, exercise what they are designed for—fulfilling specific functions. This ability affords design practice the oft-quoted title of a problem-solving activity, at least in part (Cooper and Press 1995, 16).

Simon (1995, 246) describes design as a “complement for analysis”, where analysis is the processing of information regarding any given intended object. Adding to Norman’s view of design as capable of crafting usability, this brings design to being also “inherently computational” (1995, 247). Simon compared design to a problem-solving activity equivalent to logic but involving the imagination (creativity).

Though this contribution has been referenced over time to attest to design’s ability to do just that, one cannot resort to this definition dogmatically (Hatchuel and Weil 2002, 19). Design includes problem-solving but cannot be simply reduced to it. Doing so would deprive design of everything else it is capable of, such as its influence on aesthetics. “There is no doubt that problem-solving is part of a design process, yet it is not the whole process” (Hatchuel 2001, 10). Manufacturers or clients that present designers with ‘design problems’ to be ‘solved’, approach them with more than mere logical problem-solving in mind.

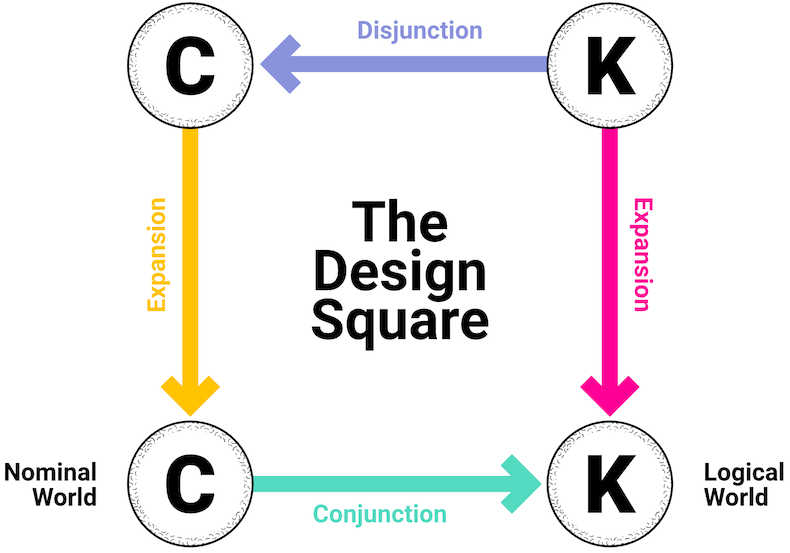

Figure 5.1: The Design Square by Hatchuel, Le Masson, and Weil (2004) explores the problem-solving process of design moving between spaces of concept (C) and knowledge (K).

As the act of designing through creation is a key actant in this research, knowledge generated through the process of designing cannot be defined in strict terms of problem-solving. Pye (1978) asserts that the decision to what form a designed thing may take is done either by choice or chance. Having a critical view of representing design as problem-solving or as an art form, he resorts to expressing how design manifests both attributes (Cooper and Press 1995, 18). A better explanation of the view of design asserted here is that of Hatchuel, Le Masson, and Weil (2004), which they present in a cyclic model of the design process (Fig. 5.1). Here information is shared between spaces of concept and knowledge. Through a series of disjunctions and conjunctions gathered information is co-expanded, resulting in a designed object of intention.

Where Simon’s view of design defined it strictly as a mechanism for problem-solving similar to logic, the design process does not afford a singular format of logic assertion (such as mathematics or sciences) to solve problems. Rather, multiple formats are presented from social contexts to crafting and technological, benefiting both concept and knowledge spaces with generated information.

5.2.1.2 Design as a process

Design may be defined as a series of steps designers undertake, to achieve or balance specified goals and constraints (Edelson 2002, 109). These goals may or may not include the potential of solving a given design problem, but certainly involves the presence of designerly intent. Iterative processes of design, development, and implementation are often associated when practising design—mentions of which appear throughout this text as well—making design a procedural activity. Edelson (2002, 109) defines the ‘design process’ as open-ended and complex invoking creativity, which in his view, presents a challenging space for researchers to characterise. He attempts to characterise the design process through the decisions made in iterative cycles he calls procedure, analysis, and solution. Cooper and Press (1995, 36) explore this through the definitions of process present in design management, a field that heavily utilises design process paradigms. In their opinion, a process in a design context is either a means for designers to exercise their skills in expanding on a problem space to achieve a relevant solution or, it may describe strategic planning invoked in the design and development. Advising against taking either definition to its extreme, they suggest achieving a balance to benefit from the idea of design as a process better.

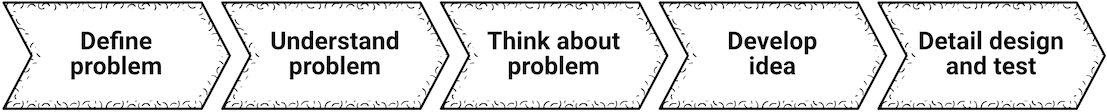

Cooper and Press quote Lawson (1990) stages of the creative process for design as one that hinges on “imaginative, intuitive or divergent thinking” to formulate solutions (Cooper and Press 1995, 22). They simplify it into a journey that starts from defining the problem to developing ideas and testing (Fig. 5.2). However, due to the nature of design as a fluid concept allowing the meshing of a multitude of disciplines, different variants of explaining the design process exist (Hollins and Hollins 1991; Walker, Dagger, and Roy 1989; Roy 1986; Fairhead 1988; L. Sanders 2008; Frankel and Racine 2010).

Figure 5.2: Cooper and Press (1995) present a simplified model of design as a process in the form a journey.

No matter how one defines the design process, all design moves in task-oriented iterations of development (Cooper and Press 1995; Edelson 2002). These iterations craft out the design procedures required to specify domain interests, processes, and people involved in the development, and may present the creation of theories, frameworks, and methodologies for research (Edelson 2002, 113).

Be it the crafting of a product, a service, or a business model, an iterative nature is fundamental to any design. When seen as a process, design allows the intermingling of varying disciplines to interject into other layers of information that may be arranged within the design. It further allows for a systemic investigation akin to that of research. The design process itself thus becomes a form of research conducted to achieve specified goals.

5.2.2 Defining Research

Having defined Design to our needs, we can now explore the second half of ‘Design Research’. Research is commonly understood as a systemic investigation intended towards generating new knowledge and usually involves proving/disproving hypothesis, the formulating of theories, facts, and accompanies a heavy association towards science and technology (Frayling 1993; Faste and Faste 2012). Friedman (2000, 48) asserts, the meaning of research stems from its Latin roots as an activity involving search and exploration. Common misunderstandings assume research has little to do with creative thought or practice and is solely a retrospective activity of formulating knowledge, compared to design (2000, 47). This, of course, is not the case as the activity of research associated with design is exploratory and concerned with both inquiry and the production of new knowledge (Frankel and Racine 2010; Cross 2007). Three forms of research may be identified here, and thus, compared to design in this manner: basic research, clinical research, and applied research (Friedman 2000; Frankel and Racine 2010; Buchanan 2001).

5.2.2.1 Basic, Applied, and Clinical Research

Basic research focuses on empirical investigations into general principles that may cover a wide variety of situations and is intended to generate knowledge on several levels (Buchanan 2001; Friedman 2000). Comparatively, applied research attempts to adapt the findings from basic research into “classes of problems” (Friedman 2000, 48) which may feed the generation of hypotheses, furthering knowledge creation. Frankel and Racine (2010, 4) second Buchanan and Friedman’s opinions that applied research may be critical to understanding design due to its traits of systemic inquiry.

Finally, clinical research regards itself with specific cases and involves the application of both basic and applied research findings (Friedman 2000, 49). Frankel and Racine (2010, 3) give the example of the design of a walking aid, which would incorporate the collection of a wide array of information from different sources such as users, environments, materials and exploration of similar products. Several factors would need to be considered in the design of this product, which would only be assessed through the collected information. Such research takes on the form of documented case studies, and gives insight into problems that expand on the original matter of concern (Frankel and Racine 2010; Buchanan 2001).

In this manner, design research involves a systemic usage of basic, applied, and clinical research. It also encompasses the analysis of information through lenses of various disciplines that may be utilised or appropriated to achieve the object of design. Friedman thus defines the role of designers, which mirrors the role of design researchers, thoroughly as such:

“Today’s designer works on several levels. The designer is an analyst who discovers problems. The designer is a synthesist who helps to solve problems and a generalist who understands the range of talents that must be engaged to realize solutions. The designer is a leader who organizes teams when one range of talents is not enough. Moreover, the designer is a critic whose post-solution analysis ensures that the right problem has been solved.” (Friedman 2000, 49)

5.2.3 The Object of Design

In either case design as a process/tool for research or design as an act of creation, a fundamental notion associated with design is that it intends to draw things together in what Binder et al. (2012, 26) call the “object of design”. Their definition of design is an activity that involves a gathering of cooperation and imagination. They explore the design process as one that requires a sense of openness and evolution that is free to end at “novel, and sometimes unexpected, solutions” (2012, 22). The notion they present is of design and research co-mingling, echoing the thoughts of Schön (1983) for whom the role of a reflective practitioner was paramount to conducting design practice. They summarise his works by explaining how “knowing and doing are inseparable” (Binder et al. 2012, 24); a key aspect of design where reflection occurs in the act of designing.

This philosophy is influenced by the works of Dewey (1938), who explored the epistemology of creative processes. For Dewey, experiences grew out of daily encounters and became the foundation for understanding. He took this forward to explore the role of aesthetics and logic, which Binder et al. explain as so:

“According to Dewey, all creative activities show a pattern of controlled inquiry: framing situations, searching, experimenting, and experiencing, where both the development of hypothesis and the judgment of experienced aesthetic qualities are important aspects within this process.” (Binder et al. 2012, 25)

This exploration of the object of design takes design into the philosophical space of phenomenology; a concept we explored in the last chapter. Binder et al. (2012, 26) place this idea on par with Latour’s object-oriented politics (Weibel and Latour 2005). They propose viewing design as capable of “accessing, aligning, and navigating among the ‘constituents’ of the object of design” (Binder et al. 2012, 26). Whereby the ‘constituents’ they are referring to are the modalities through which interactions take place with the object of design; vis-à-vis, things or representations of things. As such, they argue that design is challenged to contend not merely with designing things, but also with matters of concern relating to socio-material assemblages of what the designed thing implies. This makes design as a construct a phenomenological enterprise that deals with knowledge creation through its many constituents, such as aesthetics, logic, experience, tactility, craftsmanship, etc.

5.2.3.1 Research as a ‘kind’ of Design

Where Binder et al. (2012) define the object of design to bring things together, their concern is with the use of design practice as a research analytic in participatory settings. This phenomenological extension of design may be equally explored through other avenues of design research. By now one may accept design research to be a subset of design, though the nature of research conducted as design research is not conventional (Faste and Faste 2012, para. 15).

Design by nature requires certain kinds of knowledge to intermingle amongst each other (Friedman 2000). There is a consensus among practitioners and academics alike that design, and many of its varieties, may be classified as practice-based as they are oft realised through their execution (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010; Faste and Faste 2012; Alain Findeli et al. 2008; Frayling 1993; Cooper and Press 1995). This entire chapter so far has been about exploring this very nature of design. As an accumulative discipline containing knowledge and information from a variety of sources understood by practice. This act of designing that is pertinent to design itself, contains all the ingredients required to fulfil it as a ‘kind of’ research-practice.

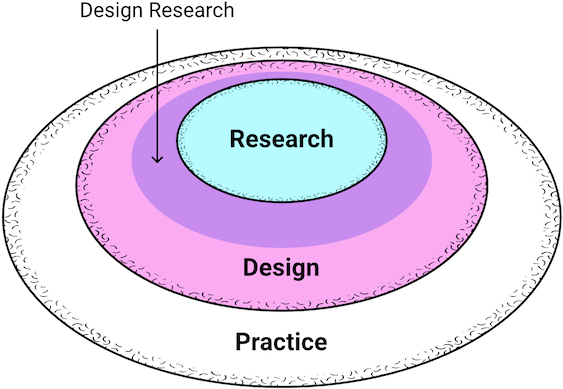

Faste and Faste (2012, para. 15) propose an alternative view (Fig. 5.3) where rather than seeing design research as a ‘kind’ of research, one may see “research [as] always a ‘kind’ of design”. They place the practice of design as a super-set encompassing design and research:

“Clearly scientists”practice" research just as designers naturally practice design…This model makes clear that all research is a subset of design practice at large, and that design research is simply the set of such methods not conventionally considered to be research." (Faste and Faste 2012, para. 15)

Figure 5.3: By seeing research as a subset of design Faste and Faste (2012) propose a view that design embodies research.

Their definition of research as a ‘kind’ of design allows for a broader acceptance of what constitutes for design research. This makes the act of designing itself a type of research, as much as, the act of researching (within the context of design) a type of design. Both views generate new knowledge through some manner of practice-based execution. Over the years, design has evolved from being a craft-oriented profession, into a multidisciplinary information-oriented engine, implementing meaningful socio-economic services, systems, and interactions (Muratovski 2010, 378). Therefore, this practice-based element of design becomes a pertinent aspect of the design process. One that allows for designers to push the boundaries of what may be catalogued as research, unearth potential problem solving and open up new meanings and understandings for knowledge generation.

5.2.3.2 Wicked Problems

Earlier on I pointed out how design involves problem-solving. The problems design attempts to address though are not conventional, as they rarely fall within the strict structures of scientific research. Rittel and Webber (1973, 160) introduced the term “wicked problems” to define complex problems within urban planning, which due to their complexity had implausible or otherwise unattainable solutions. The term was later appropriated to acknowledge design’s ability to function within complexity through design thinking by Buchanan (1992).

Earlier attempts at defining design research involved attributing scientific research approaches to design (Frankel and Racine 2010). This meant design was explored in a sequential methodology, similar to science. Rittel and Webber (1973, 160) attempted to differentiate societal problems from scientific ones by presenting them as “wicked” and “tame” problems respectively. Ergo, explaining how problems relating to human experience are not the same as those relating to nature, or science. As these problems tend to be more complex in nature, involving multiple facets and consequences, a sequential methodology for understanding such complexity was thus inadequate (Cross 2007; Gedenryd 1998).

Since design relates to matters of human experience, these wicked problems transcend naturally into concerns of design. An example of a wicked problem hard-pressed for a scientific solution alone would be climate change. An intermingling of multiple disciplines is required to facilitate scientific solutions, which would further need to be exercised through some manner of design.

Buchanan (1992, 17) speaks of the designer as one who is concerned with quasi-subject matters which exist within the problems they explore. Essentially, their understanding of a problem defines further problems as they are revealed. The quasi-subject matter is “indeterminate” and awaiting to be made specific through its acknowledgement. Buchanan goes ahead to explain how by doing this, the wickedness of the problem is removed. Giving the example of a client brief he says:

“A client’s brief does not present a definition of the subject matter of a particular design application. It presents a problem and a set of issues to be considered in resolving that problem. In situations where a brief specifies in great detail the particular features of the product to be planned, it often does so because an owner, corporate executive, or manager has attempted to perform the critical task of transforming problems and issues into a working hypothesis about the particular features of the product to be designed. In effect, someone has attempted to take the ‘wickedness’ out.” (Buchanan 1992, 19)

Wicked problems require to be resolved as a collective of exchanged thoughts, ideas, artefacts, and services (Dubberly 2017, 162). This is perhaps why design functions so well with wicked problems. It is, after all, the object of design to gather together necessary elements to facilitate a design agenda.

Therefore, when considering what is design research, one may see it as a systemic inquiry into the object of design enacted through a process of design. This inquiry involves investigating the myriad problem spaces within an area of focus with the intention of resolution, and usually tends to wicked problems. Furthermore, due to the nature of design as a practice-based activity, the act of designing is a pertinent element that allows for research to be embodied within the object of design.

5.3 Research through Design

The previous lengthy definition of design research was necessary to establish a baseline for why RtD as a methodological framework was utilised for this research. I will now define RtD and its place in this work. As an ideology RtD comes from one of three categorisations of design research presented by Frayling (1993). His Research in Art and Design is by far the most cited document in design research (Friedman 2008, 154), with many academics using his categories and debating over formulating further design theory and methodologies (Godin and Zahedi 2014; Faste and Faste 2012; J. Bardzell, Bardzell, and Koefoed Hansen 2015; Cross 2007; Downton 2003; Jonas 2007; Friedman 2003). In the document Frayling (1993) attempts to differentiate between the role of a researcher in science and that in the arts, all the while comparing against what it means to research within the context of design.

For him, an artist is one that works in an expressive form rather than a cognitive one. The artist works towards personal development, rather than understanding the nature of things. Designers, he defines, are concerned with craftwork and doing things instead; through hands-on experimentation, involving a level of aesthetic appreciation, and imagining things to achieve a certain effect. Researchers, on the other hand, rely on critical rationalisation to formulise or refute hypotheses through defined methodologies. Using this, he argues for a linkage between science and art—which is seen in design practice—and suggests, adjusting the way research is conducted within these disciplines to accommodate the overlap.

Frayling’s three categories focused on both art and design in this way. Many have since appropriated and/or reworded them to fit better with design research (Cross 2007; Faste and Faste 2012; Jonas 2007; A. Findeli 1999). As such, the general three categories of design research are as follows:

Research about/into Design generally occurs in academia where the focus is to contribute towards the greater knowledge of design research and its implications as a scientific study into design. It incorporates documentation of design history, phenomena, and what the object of design contends to.

Research for Design focuses on guiding the practice of design by documenting processes done by professionals and practitioners. Here the designer is treated as the subject matter as opposed to the designed object, where research is intended to aid in the development of design.

Research through Design comes closest to the practice of design itself as it combines processes in practice to embody the knowledge generated from design research within a designed artefact. Here the designer/researcher practices design to enact their research through iterative experimentation associated with the design process.

As design has evolved into an industrial discipline, compared to earlier definitions of it as a supplement to art, Frayling’s proposal to establish new categories of design research aided in future probing and inquiry (Friedman 2008, 157). Friedman has been critical of this though, exclaiming that some of these categorisations of design should not be mistaken for a factual representation of design practice. That said, as a probe into the possibilities of design research, Faste and Faste (2012) present a clearer account of defining design research categories that better fit with the three kinds of research (basic, applied, and clinical). They do this through an understanding of how research approaches design and vice versa.

5.3.1 Approaching Research through Design

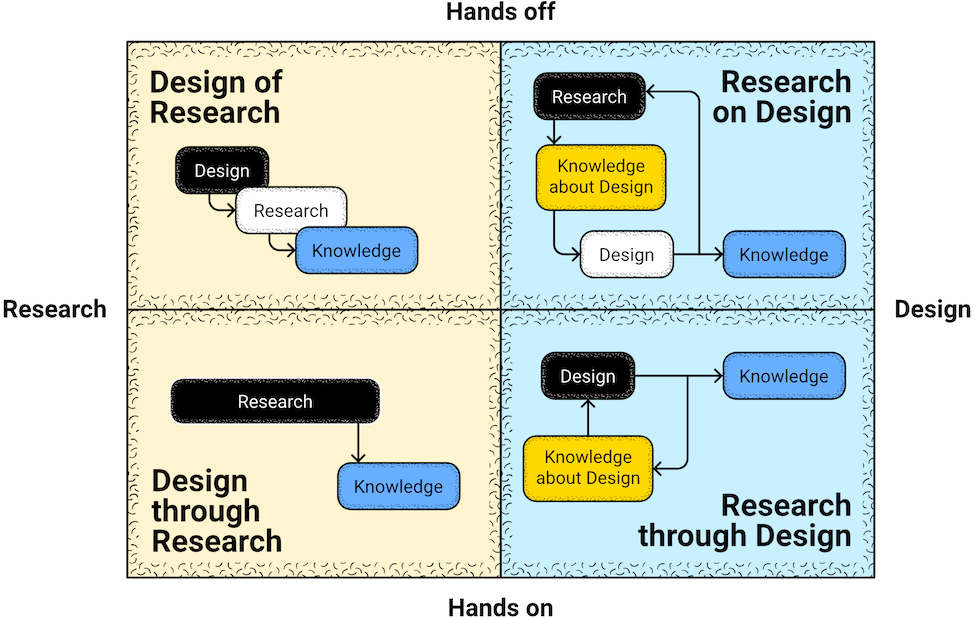

Faste and Faste (2012, para. 17) present four modes of design research (Fig. 5.4) where two they consider a “hands-off” approach and two a “hands-on” approach. They acknowledge both the iterative nature of design and the sequential nature of research in their model, incorporating them in their hands-off/hands-on paradigm. The four categories they present are: Design of Research and Research on Design (as hands-off), Design through Research and Research through Design (as hands-on).

knitr::include_graphics(rep("figures/ch5-approaching_rtd.png"))

Figure 5.4: Expanding on Frayling’s earlier classifications Faste and Faste (2012) present four modalities of design research each representing Frayling’s view of design research as either being a hands-off or hands-on approach.

Though I could explore all the modes presented by Faste and Faste in more detail, as this work focuses on RtD deviating towards these other areas of design research is beyond the scope of this thesis. What should be noted is that they are all, essentially, are expanded appropriations of Frayling (1993) original categories. The comparison between them and RtD is what makes it more important to our discussion.

Faste and Faste (2012, para. 23) rename RtD as “embedded design research”, because of its approach to conducting ‘research’. Where the others deal with the broader perspective of design as a discipline, RtD relates with the core rhetoric of the design process as a practised activity. One where knowledge is embedded as much in the designer’s design as it is in the world the design occupies (2012, para. 21). Many academics and designers associate RtD, with creating designed artefacts that indulge in societal change through their enactment (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010; Swann 2002; Binder and Redström 2006). J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi (2010) catalogue a background of RtD by referencing its different considerations over time, along with its heavy association with wicked problems. Alain Findeli et al. (2008) present RtD as having traits of the other forms of design research (about and for):

“Proper research through design could thence be defined as a kind of research about design [more] relevant for design, or as a kind of research for design that produces original knowledge with as rigorous [and demanding] standards as research about design” (Alain Findeli et al. 2008, 71)

Basballe and Halskov (2012, 59) understand RtD as an activity affording researcher’s active engagement with the design process. An activity that is further communicated to feed the greater expanse of design theory and knowledge through academic ventures. Godin and Zahedi (2014) discuss the many faces of RtD as named by different authors. Some of the more common comparisons are with constructive design research or practice-led research. They express discontent towards these different definitions of RtD as, in their opinion, they lack a consensus towards how RtD and its effects should be discussed.

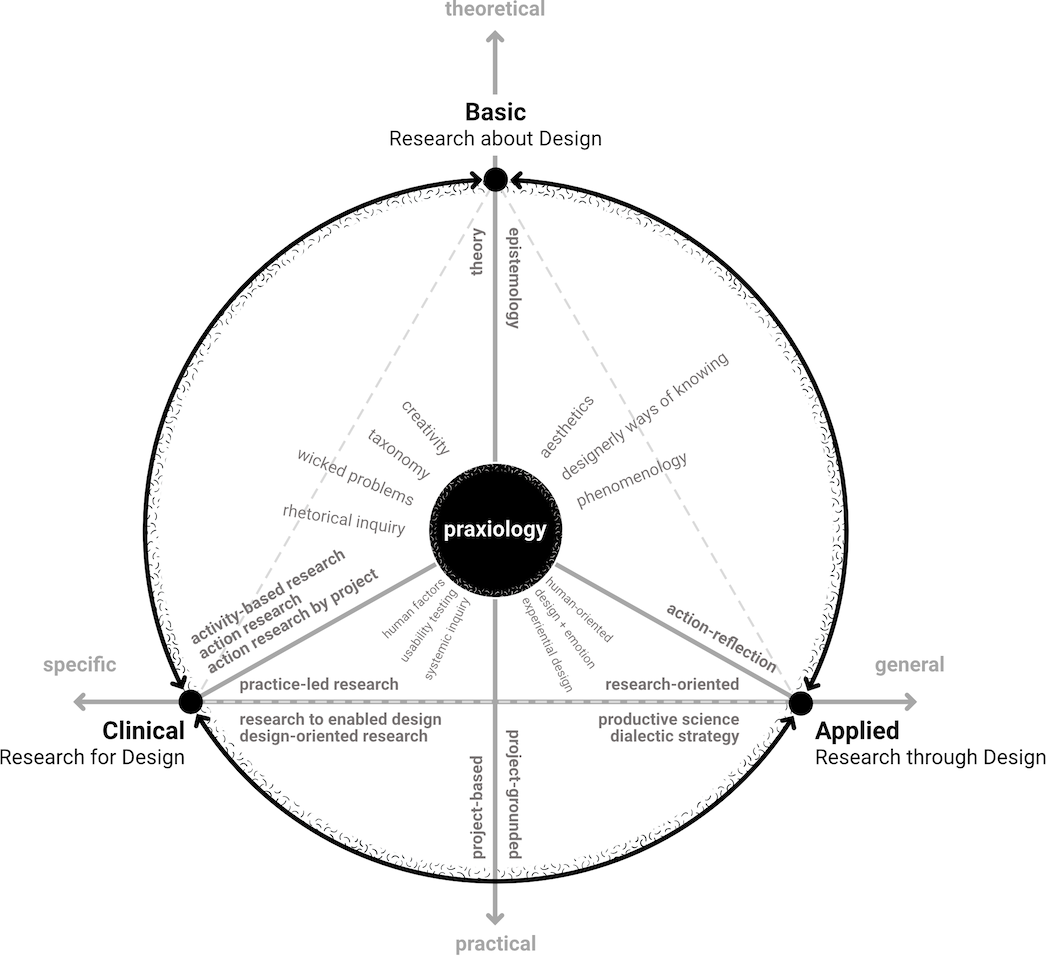

Figure 5.5: Frankel and Racine (2010) present a cyclic relationship between the different kinds of design research exploring how design is exercised in different manners moving between theory and practice

In an attempt to map a relation between the different design research categories, Frankel and Racine (2010, para. 40) build upon Friedman’s work and illustrate a flow of information between research for design, research about design, and research through design, occurring in a cyclic manner (Fig. 5.5). Their illustration aligns the three categories as vertices on a triangle with clinical, basic, and applied research alongside their respective categories. The alignment of RtD, to no surprise, is as an applied research approach enacting action-reflection methods. Thus, the readiest comparison can be made between RtD and Action Research methods commonly used in social sciences, as they both incur iterative procedures that include stages of planning, acting, observation, and reflection (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010; Long 1991; Binder, Koskinen, and Redström 2009). Swann (2002) acknowledges research through practicing design to invoke nearly identical procedures to those of Action Research, implying design research to have appropriated RtD from the more common methodology.

There is a consensus among these researchers though, that RtD has the ability of “broadening the scope and focus of designers” (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010, 311), allowing them to challenge constructs more readily in light of given technologies and practices. Another thing many researchers agree upon irrespective of the end intentions or goal of research, is how RtD tends to matters of the future (Binder and Redström 2006; J. Zimmerman, Forlizzi, and Evenson 2007; Godin and Zahedi 2014; Swann 2002; Faste and Faste 2012).

The variant definitions of RtD assume a common similarity where they all assert the physical practising of design as a form of research and knowledge generation. This is conducted through the creation, execution, and collection of artefacts, prototypes, models, and/or portfolios; often in a practice-oriented format of research.

5.3.2 Practice-based Research

As discussed above and repeatedly, design is very much entranced with the act of designing. As such, a wide array of examples can be found that utilise the practising of design as an activity within research in the manner of an engine for knowledge generation (Rose 2015; J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010; Coulton et al. 2019; Encinas and Blythe 2016; Toeters et al. 2013; Cila et al. 2017; J. Lindley, Akmal, and Coulton 2020; J. Bardzell, Bardzell, and Koefoed Hansen 2015). J. Zimmerman, Forlizzi, and Evenson (2007, 497) tout the designers’ ability to create products capable of transforming worlds from their “current state to a preferred state”, they also agree that RtD involves an integration of multiple disciplines. The point raised here is that these newer states are opened to an empirical investigation that is influenced by transdisciplinary viewpoints and interventions. Regarding the construction of ideas in the process of design, Stappers (2007) indicates the ‘act of designing’ itself as a core conduit, utilising a procedural confronting of present technologies, theories, phenomenon, and other elements to build towards a testable designerly artefact.

On this very note, as findings of their work using RtD, participants in a study conducted by Zimmerman et al. concluded how “RtD lead to new artefacts (products, environments, services, and systems) where the artefact itself [became] a type of implicit, theoretical contribution” (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010, 314). Moving on they explain how these artefacts invoked a power that allowed a codification of the designer’s intents and understandings.

Stappers, Sleeswijk Visser, and Keller (2014) explore the role of prototyping in practice-based design research, comparing it to design-inclusive research methods. They conclude that where one involves the design as a necessary in-between step of research and hypothesis, it effectively separates the designer from being an active part of knowledge generation. Compared to that, RtD makes the act of designing an essential element of knowledge generation conducted by the designer. In their opinion, one approach thus becomes theory-driven hence stunted, while the other is driven by phenomenon thus more explorative. They agree that practice-based research in this regard, stresses a designed object to be more “communicative” (2014, para. 7).

Design strives to synthesise different concerns in an investigation of “disparate forms of knowledge”, essentially necessitating research (Faste and Faste 2012, sec. 4, para. 1). As a discipline rooted in craftsmanship and a history of creation, the practice of design cannot be removed from the discipline of Design. Faste and Faste (2012) argue that generated designs facilitate and further acknowledge the presence of design process knowledge that is embedded in the designer, and the world the design exists in. They further argue, that in this manner RtD when compared to traditional research methods “disseminate knowledge through broader means” (2012, sec. 2.4, para. 2). They quote observations by Biggs (2002) regarding the role of the artefact in design research, as “embody[ing] the answer to the research question” (Faste and Faste 2012, sec. 2.4, para. 2). Essentially, by embedding knowledge into the activity by design, the research and information extracted from the activity are only more enriched.

5.3.3 Ideology or Methodology?

Praise for RtD as an approach aside, there is a level of contention that must be addressed as well. To begin with, RtD as a research paradigm is not as mature (Alain Findeli et al. 2008; Stappers, Sleeswijk Visser, and Keller 2014; Höök and Löwgren 2012; Brandt 2007; S. Bardzell et al. 2012). Though progress in design research is indeed amplified beyond publications when prototypes, frameworks, and artefacts allow new paths for observing phenomenon (Stappers, Sleeswijk Visser, and Keller 2014, 166), RtD and similar practice-based research lack “methodological soundness and scientific recognition” (Alain Findeli et al. 2008, 72). Alain Findeli et al. (2008, 73) present the relationship between theory and practice as the culprit for this. Where on the one hand the claim is for practice to be an important aspect to the building of theory, it becomes significantly more challenging to define practice as a repeatable and redistributable process.

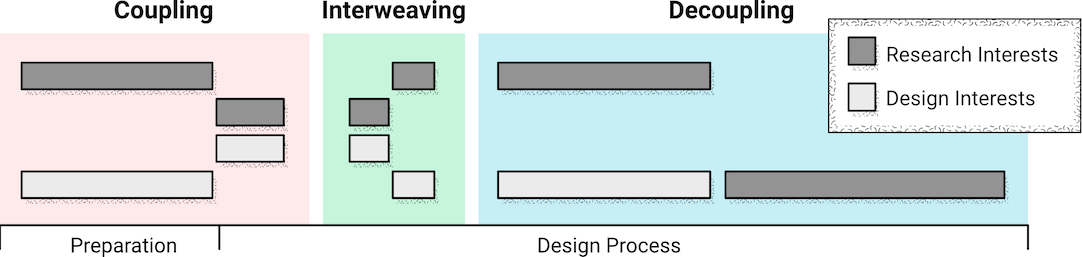

Figure 5.6: Basballe and Halskov (2012) see the RtD process as a sequence of dynamic stages interweaving design and research practices that start with gathering information and ordering them in a way that areas of interest overlap to focus on individual areas of design and research

Basballe and Halskov (2012, 65) attempt to break down the RtD process as three dynamics that appear in sequence through every project: coupling, interweaving, and decoupling (fig. 5.6). Their opinion is that every RtD project undergoes an initial coupling stage that involves framing levels of constraints to be exercised throughout. This is followed by an interweaving of research and design interests which are intended to influence each other as processes and validations of methods are exercised. Finally, the project enters a decoupling phase where the design researcher focuses on a specific area of interest extracted from the process; this could be either design or research, depending on what is of interest and at what stage the decoupling occurs. Thus, in appearance RtD is very similar to a regular design project executed by practising design (Godin and Zahedi 2014, 1677). On that, addressing the problems in design research Friedman expresses:

“One of the deep problems in design research is the failure to engage in grounded theory, developing theory out of practice. Instead, many designers confuse practice with research. Rather than developing theory from practice through articulation and inductive inquiry, some designers mistakenly argue that practice is research.” (Friedman 2008, 154)

Designers, practitioners, researchers, and participants of design research alike experience the interplay of practice and theory differently. The bane of RtD in this regard is the fact that it is an applied research paradigm. The earlier stages of RtD are often referred to as ‘the fuzzy front end’ due to its association with different levels of creativity, analysis, making, dissecting, and processing. This presents RtD as a non-linear approach compared to the logical linear approaches required for forming many methodologies (Stappers, Sleeswijk Visser, and Keller 2014, 174).

In his original document, Frayling (1993) distinguished RtD from the other research categories, particularly considering art and design. Where the goal for researched design is understanding the design over knowledge, RtD instead, must be about understanding knowledge over the design. Godin and Zahedi (2014, 1670) argue for the contention here, that in RtD knowledge and understanding is the result of exercising design-practice and making that is embodied in the design artefact.

Godin and Zahedi (2014, 1676) further give a compelling definition of RtD in that it can be defined “by what it is not”. They argue that the artefact is not the goal of an RtD project, rather, it is and should be the generation of knowledge. Secondly, they claim RtD may not provide a level of predictability that is oft required for traditional research; though, that is also a contention associated with other avenues of design research. Therefore, classifying RtD as a methodology at this stage is too early as the field itself is not mature enough. At the same time, the practice of design is inevitable within design research, ergo, an essence of RtD is present in almost all forms of design research. As an ideological stance within design research, it makes more sense to execute RtD rather than proclaim it as a bonified methodology.

5.4 Conclusions

The above definitions of both design research and RtD intend to highlight their unique potentials in executing the object of design. The mapping presented by Faste and Faste (2012) of research as a kind of design towards a definition of hands-on researching through the application of design methods, suggests that RtD artefacts inhibit a cyclic generation of unique knowledge. Artefacts or concepts that emerge from this process are enriched through a broader understanding of ideologies embedded in the given problems and from those acquired in the process of understanding those problems. Though towards the end of the last section I refrained from classifying RtD as a methodology, for the purposes of this research it is utilised as a methodological framework for the reasons defined in this chapter.

Building upon all presented above, this research attempts to represent RtD as Gaver (2012) defines it. His opinion is that RtD should be “appreciated for its proliferation of new realities” (2012, 941), and ability to annotate the artefacts it creates. Explaining what research should expect from RtD, he goes on to say that artefacts created by design are embodied with the myriad choices taken by their designers, which would otherwise be impossible to acquire in non-practice-based formats (such as writing). This makes the design artefact, and the information extractable from them, “indispensable to design theory” (2012, 945).

Regarding the contention between theory and practice, Gaver (2012, 939) contrasts designs concern with finding the ultimate solution or particularly with sciences association to the ‘truth’. By doing this he raises a point, that when practising design the search for the ultimate truth is extracted from the artefact as annotations. Compared to science which relies on the presence of facts, these annotations build a case for design theory that explain and reference “features of ‘ultimate particulars’, the truths of design” (2012, 939).

As this research contends with understanding concepts of an unorthodox nature through philosophical inquiry into the phenomenon of human to non-human interactions, an iterative RtD process of design research is most applicable. It is capable of enriching the discussion of designing for IoT through the application of philosophical discourse and practice-based design research.

Gaver’s expectation of RtD is of mutual collaboration between academics, designers, and researchers. Whereas as a research approach, perspective, or potential methodology, it is afforded a level of elaboration between practitioners that is both critical and discursive. That said, the level of research conducted in and around RtD contend to its benefits outweighing the potential conflations in arguments. Alain Findeli et al. (2008, 82) argue for design research to be transdisciplinary to be able to nourish the design project. RtD has been known to exercise the object of design clearly and effortlessly through processes of “composition and integration”, making it suitable for both early stages of forming nascent theory, and developing later comprehensive constructs (J. Zimmerman, Stolterman, and Forlizzi 2010, 317).

This research takes on a transdisciplinary approach at combining applied design knowledge and practices with theories of philosophy and technical understandings of IoT. In that sense, the framework presented by RtD as a research methodology allows for an expansion of knowledge into different areas of design, philosophy, and technology. Though an overarching methodology in this research, it becomes more enriched when the freedoms of an attitude of playfulness are incorporated as the next chapter highlights.